Hog producers who are evaluating forward price or margin coverage have many different risk management tools to help address their varied market exposures. In addition to physical and exchange traded instruments, Livestock Risk Protection (LRP) and Livestock Gross Margin (LGM) can provide valuable protection for certain price risks. It is important for producers to understand the features and merits of these two programs so they can decide which product (or which combination of products) is a good fit for their specific operation. Both programs can offer potential advantages, but they are different and thus producers need to carefully consider direct comparison between the two.

LRP is designed to protect hog price, specifically the CME Lean Hog Index value, while LGM is a margin-based program that offers protection based on a standardized crush formula incorporating corn, soybean meal, and lean hog futures prices. Relatively recent improvements to both LRP and LGM have increased their risk management value and made them more attractive to producers. As a result, participation has risen significantly for both programs over the past several crop marketing years.

Figure 1. Increased Industry Usage

For LGM, in July 2020 subsidies were applied to the insurance premium and the premium due date was moved to the end of the coverage period. Starting in July 2021, LGM was offered weekly versus the previous monthly offering.

While not directly comparable, historical studies have been done to determine whether LRP or LGM has offered a better return for a given premium cost and deductible. Given most producers using LGM will elect the $10 deductible, and that there is also a 6-month horizon on coverage with this program, we can compare the historical performance of using LRP versus LGM under these constraints. Figure 2 shows that while returns have been higher for LGM as the deductible increases to the $10 level, the advantage shifts to LRP with a lower deductible for more at-the-money coverage (the typical LRP use case).

Figure 2. LRP vs. LGM Deductible Analysis

While the above comparison is a historical fact, further analysis is vital to understand the differences and maximize the opportunity presented by both programs. There are several important limitations to these types of direct comparisons. First, it is important to note that a direct comparison is only possible on the days LGM was offered (monthly or weekly versus daily for LRP). Next, the timing of improvements to LGM (which raised both the attraction of using LGM and the opportunities for its use) coincided with years in which we have witnessed a sharp increase in both corn and soybean meal prices. Also, because LRP only protects the hog price, this analysis does not take into consideration any independent feed coverage a hog producer using LRP may have – either through raising their own crops or protecting against increased cost through other channels. Last, because LGM is only offered 6 months into the future, the comparison ignores the fact that utilizing LRP further out in time potentially increases its benefits. Below are some points that informed producers should weigh when comparing and using these two valuable products.

Features of LGM:

Based on publicly available data, most producers who use LGM have chosen an approximately $10 per head deductible and will typically add coverage in at least 2 months to optimize the premium subsidy. By increasing the deductible, producers can reduce the insurance premium by a significant percentage of the change in deductible. Another attribute of LGM is that it has no annual head limit (whereas LRP has a 750,000/year head limit) which can be attractive for some larger producers. LGM may also be a good fit for shorter term coverage because the nearest available LRP expiration is 13 weeks out in time. LGM is also potentially applicable in situations where producers are less active risk managers or for addressing tail risk in conjunction with other risk management strategies.

Features of LRP:

LRP is available 52 weeks in advance, providing producers an additional 6 months to implement risk management strategies if presented with an attractive opportunity. Because LRP is based solely on hog prices, a producer can immediately supplement LRP coverage with certain exchange traded instruments if it fits their bias and risk tolerance. For many producers, the CME Lean Hog Index (which LRP settles against) more closely tracks their specific packer contracts and can therefore reduce basis risk. Also, because LRP is offered most days, producers can select coverage end dates that address periods during the year which have notoriously weak basis (late December and early January for example). Lastly, producers that also grow some or all of their corn needs might not have the feed exposure addressed by LGM.

Fortunately, starting last summer, producers can use both LGM and LRP together if the endorsements don’t end in the same month. This change should lead producers to increasingly incorporate both programs into their risk management plans. There are pros and cons to each program, and understanding these benefits and limitations should help guide their uses. An informed producer can choose the combination of risk management tools that best fits their operation and adds value by maximizing the unique advantages of each program.

Please contact us to learn more about how to optimize the use of these valuable insurance tools as part of a comprehensive risk management strategy for your hog operation.

As 2019 closes out, hog producers are no doubt feeling better about the upcoming year compared to what is being left behind. To say this year was tumultuous for the industry is putting it mildly. Months of uncertainty with escalating confrontation between the U.S. and China has given way to a first phase trade agreement that could lead to significant increases in pork shipments among other agricultural commodities. Meanwhile, ratification of the USMCA will restore favorable tariff treatment for U.S. trade across the borders and likewise be beneficial for U.S. pork demand. Furthermore, the new year will also usher in a return to preferential tariffs for agricultural exports to Japan where the U.S. lost ground to competitors after withdrawing from the TPP. It has been said that the confrontation with China in particular has curtailed the ability of the U.S. to supply the country with a reliable and affordable supply of high quality pork as the nation has seen its own domestic swine herd devastated by ASF over the past year and a half. While their demand for pork from all origins including the U.S. will certainly help to support prices in the upcoming year, it is also important to keep in mind the supply situation and its impact on price.

In the December WASDE report, USDA updated their projection for 2019 U.S. pork production to 27.708 billion pounds, up 74 million from the November estimate of 27.634 billion, and 406 million above their estimate back in June as hog and pork supplies in the second half of the year came in well above expectations. The current projection for 2020 U.S. pork production is 28.694 billion pounds, an increase of 3.6% over the current year and roughly in line with both the percentage increase in the Dec 1 all Hogs & Pigs inventory year-over-year as well as the Sep-Nov pigs/litter from the latest quarterly inventory report at 103.02% and 103.07%, respectively. The percentage increase year-over-year in the heaviest weight hog categories continues to be larger than what would have been expected based on previous surveys, and this is something that market participants will continue tracking in the new year as we move into 2020.

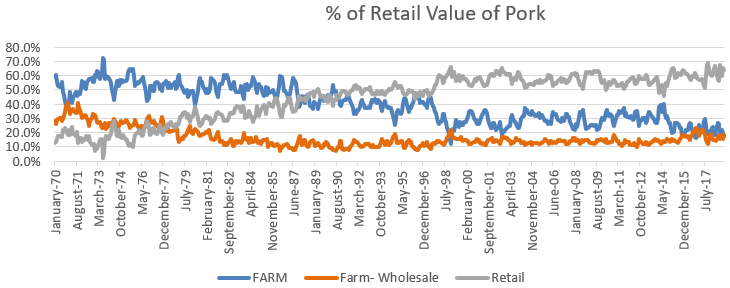

This brings up an important point. While the demand for pork is obviously quite strong, pork demand and hog demand are not the same thing. At the end of the day, producers’ revenue and profit margin are ultimately determined by the price of hogs they are delivering. While this is obviously correlated to pork value, it is important to remember that they are different. Figure 1 shows the retail value of pork broken down by component going back to 1970. These include the farm, wholesale and retail shares of the total price. What you will notice is that the retail value or share now makes up a majority of the total retail pork price at around 60%, with both the farm and wholesale values comprising about another 20% each of the total pork value. Another thing you will notice is that the retail value or share of the total price has gradually been increasing over time with the wholesale and especially the farm value shares declining since 1970.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/meat-price-spreads/)

Another way of thinking about this is that over time, the retailer has taken a larger share of the total pork dollar, with both the packers/processors and producers losing ground. There are a couple inflection points on the chart including 1998 and 2015 where the farm share lost ground relative to the preceding periods. These both corresponded to supply-side market shocks, although for different reasons as the former period concerned inadequate processing capacity relative to the market supply of hogs while the latter related to production losses resulting from PEDv. There has been much focus over the past few years on the strength in pork cutout value relative to negotiated cash hog prices. There is perhaps also a sense that much of the vertical integration we are now seeing in the industry may be in part a result of increasing retailer leverage.

The supply side of the market will definitely be a big influence over price in the coming year, even though the focus will obviously be on demand. In terms of demand, USDA is currently forecasting a 12.8% increase in exports for the coming year, with 804 million pounds of additional pork being shipped during 2020 compared to 2019. This forecast was also made with the assumption that existing tariffs would remain in place. Given expectations for China to remove tariffs on U.S. pork, some estimates are now as high as a 1.5 billion pound increase in exports, and that will likely be needed if prices are going to move significantly higher in the new year.

Even with the 800 million pound increase to projected 2020 exports, total pork use per capita is forecast essentially the same next year at 52.6 pounds versus 52.7 in 2019. Looking at the bigger picture of total red meat, and especially red meat together with poultry, per capita use in 2020 is projected at 225.6 pounds compared to 224.2 in 2019 and 219.5 in 2018. Given expectations for a dramatic expansion in the broiler industry, there will be no shortage of protein to consume in the domestic market. As a result, hog producers better hope that peace prevails on the trade front in the coming year. Anything indicative of either larger hog supplies and pork production, or lower export demand will not factor favorably on the price outlook as the domestic market will already be saturated with inventory. The economic landscape will also be important moving through 2020. Domestic demand has no doubt been aided by continued growth and historically low unemployment while inflation has held in check. While this outlook is forecast to continue for the foreseeable future, any signs of recession given the late stage of the business cycle would likewise not bode well for the market.

In terms of strategy, hog producer margins continue to look favorable into 2020, with positive returns projected through Q3 between the 75th and 87th percentiles of historical profitability over the past decade. While Q4 margins are not as strong, they are close to breakeven which is better than where spot margins for this current year’s quarter are finishing out. With the price recovery we have seen over the past month in the hog market, option implied volatility has come down although it remains very high from a historical perspective.

Perceived risk is still quite large in both directions, so producers need to weigh their comfort level to this potential exposure as they consider hedge strategies. As an example, if ASF were to arrive in the U.S. and close off our export market, are you comfortable with the degree of protection you would have to significantly lower prices? On the other hand, if summer hog prices were to rise back above $100 or higher, are you ok with the percentage of your production that will be capped and the opportunity cost associated with that? Everyone will have different answers to these questions, but it is a good exercise to take time considering as we begin the new year.

For more help on evaluating specific strategy alternatives or to review your operation’s risk profile, please feel free to contact us. There is a risk of loss in futures trading.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.This is a preliminary assessment of the Dairy Revenue Protection program based on the information available at the time of publication. Additional information may be added or updated as the program becomes available to producers on October 9, 2018.

Background

Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) is an insurance program administered by the USDA under authority of the Federal Crop Insurance Act. DRP is a voluntary risk management program designed to protect dairy producers against declines in quarterly milk revenue below a guaranteed coverage level on a producer declared milk production quantity. Premiums are due at the end of the quarter being insured rather than paid as an upfront cost once the coverage begins. The Government will subsidize the premiums at a rate dependent upon a producer’s declared coverage level.

DRP can be used in conjunction with agricultural support programs such as Margin Protection Program (MPP) as well as a complement to numerous exchange-traded products and risk management strategies available.

Important Program Features

Enrollment Periods:

Enrollment for the DRP program begins on October 9th. The first quarterly insurance period available for purchase will be Q1 (Jan-Mar) of 2019. Through December 15th, 2018, a producer will have the option to purchase coverage for five consecutive quarters, beginning with Q1 2019 and ending on Q1 2020. On the 16th day of the last month in a quarter, sales for a nearby quarter end while sales begin in the next deferred quarter. For example, on December 16th, sales for Q1 2019 are no longer available while sales for Q2 2020 begin. Premium payments are due upon the conclusion of the quarterly period being covered.

DRP will not be sold on days where monthly USDA Milk Production, Dairy Products, and Cold Storage Reports are released. Milk or dairy prices that experience a limit up or down move in the futures markets will not be available for determining the quarterly expected revenue, thus DRP will not be sold on days with limit moves.

DRP Pricing Options:

DRP offers two unique pricing options: a Class Pricing option & Component Pricing option. The pricing options are designed to allow producers customization of their price elections to more accurately reflect their price risk. Every producer has the ability to choose which pricing option is a better fit for their price risk, comfort-level, and ultimately the dairy operation as a whole.

The Class Pricing option uses a weighted average of Class III and Class IV milk prices, declared by the producer, as a basis for determining coverage and indemnities. The Component Pricing option uses the component prices of butterfat, protein and other solids as a basis for determining coverage and indemnities. Under this option, the butterfat and protein test percentages are declared by the producer to establish their insured milk price.

Covered Milk Production:

Each dairy producer declares an amount of quarterly milk production to insure under the DRP program. There

are no minimum or maximum volume requirements on covered milk production, and multiple quarterly coverage endorsements for the same quarterly insurance period are allowed, although they cannot cover the same milk. In this way, a producer may make elections that vary by coverage levels as well as by milk pricing options.

The amount of declared milk production, among other factors, will be used to determine premium cost and final revenue guarantee for each quarterly coverage endorsement under the DRP program.

Coverage Level:

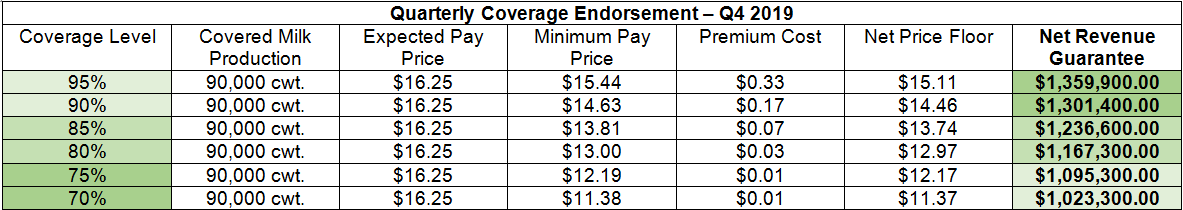

Quarterly insurance coverage levels will be available from 70% to 95%, in 5% increments. This coverage level determines the final revenue guarantee that a producer will receive on their covered milk production. The magnitude of the government subsidy paid towards the program’s quarterly premium is also determined by the producer’s elected coverage level. A producer does not directly choose their premium subsidy under DRP, rather, the subsidy is dependent upon a producer’s declared coverage level, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Using the Class Pricing Option, Figure 2 shows a producer’s price floor, or minimum pay price, at each available coverage level with an expected Class III & Class IV weighted-average price of $16.25 and 9,000,000 pounds (90,000 cwt) of covered milk production for Q4 2019. The minimum pay price is first calculated as follows:

Minimum Pay Price = (Coverage Level x Expected Pay Price)

This will be used to calculate the final revenue guarantee on their Q4 2019 quarterly coverage endorsement under the DRP program. Premium costs here are arbitrary and do not genuinely reflect DRP premiums.

Figure 2:

The net price floor set by a producer’s quarterly coverage endorsement equals their minimum pay price minus the premium paid, which would then be multiplied by the covered milk production to find the policy’s final, premium-adjusted revenue guarantee.

Net Revenue Guarantee = (Minimum Pay Price – Premium Cost) x Covered Milk Production

Notice the nature of the relationship between coverage level and subsidy received. This inverse relationship represents the tradeoff between final revenue guarantee and magnitude of a premium’s subsidy. The greater the government subsidy on the premium, the lower the final revenue guarantee, and the higher the ‘deductible’ on the quarterly insurance coverage.

How Does DRP Relate to My Revenue?

Dairy Revenue Protection provides protection from a decrease in the final milk revenue and a producer’s actual revenue on a specific producer-declared quantity of milk production. The discrepancy between the guaranteed quarterly revenue level under the DRP program and a producer’s actual milk revenue on this milk production is caused by variation in market prices over time and natural fluctuations of milking cow yields among states and pooled production regions.

DRP is not designed to insure against revenue losses caused by:

- Death of dairy cattle;

- Other loss, disease or significant decline of milking herd; or

- Other farm-level losses or significant damages of any kind

- Mandatory deductions at the plant for balancing costs

Class Pricing Option:

The Class Pricing option uses a blended Class III and Class IV milk price, based off average butterfat and protein test values of 3.5/3.0, as a framework for determining coverage, premiums, and indemnities. Under the Class Pricing option, a producer declares their Class III price weighting factor between 0 – 1.00. The default Class IV weighting factor is then 1.00 minus the producer-declared Class III weighting factor.

For example, if a producer declares a Class III price weighting factor of 0.50, then the default Class IV price weighting factor would equal (1 – 0.50), or 0.50. These weighting factors imply that this producer’s expected milk revenue will be weighted on 50% of the Class III price plus 50% of the Class IV price. When determining the price weighting factor, the Class III plus Class IV weights must equal 100% under DRP guidelines.

Under the Class Pricing Option, a producer’s expected pay price is calculated by their weighted average Class III & Class IV price average over each month of the policy’s quarter. Figure 3 shows a hypothetical calculation for the expected pay price for Q4 2019 assuming a Class III weighting factor of 50%.

Figure 3:

Component Pricing Option:

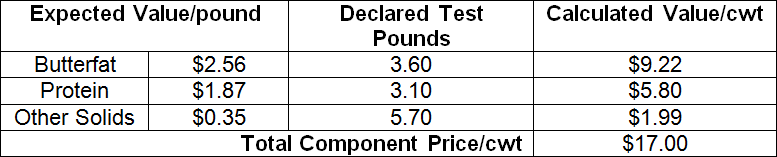

Under the Component Pricing Option, the producer declares their butterfat and protein test pounds. The other solids test is fixed at 5.70 pounds per 100 pounds of milk. The elections of butterfat and protein test pounds allow a producer to establish coverage for prices that can accurately mirror their expected milk components.

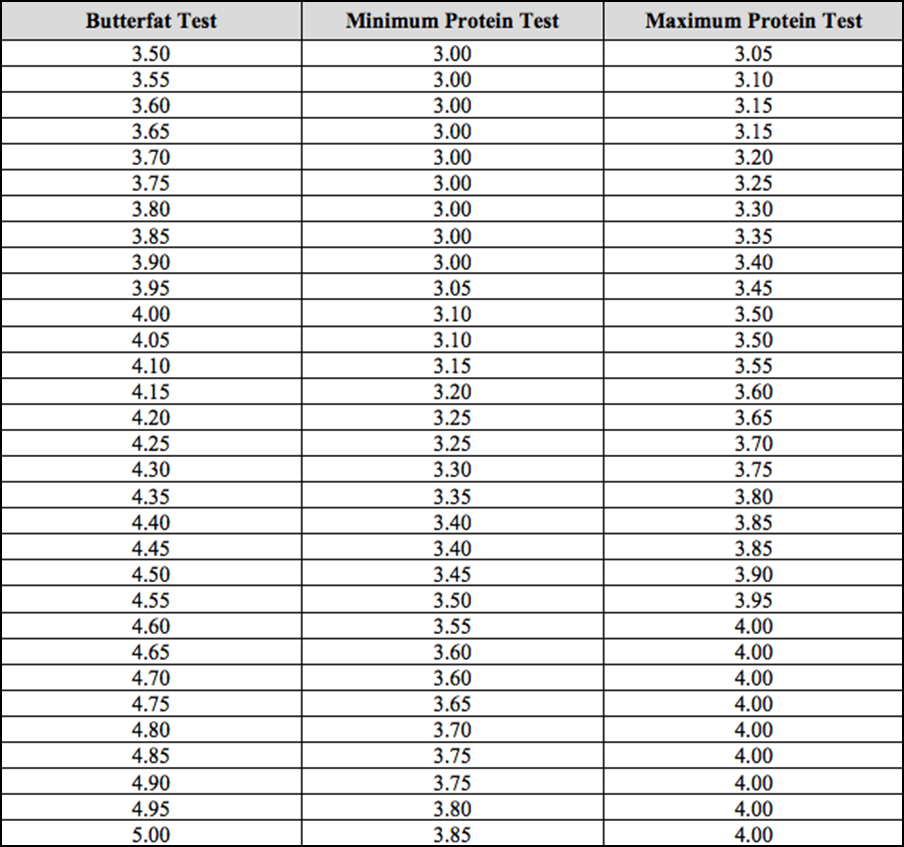

Under DRP guidelines, declared butterfat test elected can be no less than 3.50 pounds and no more than 5.00 pounds, in 0.05 pound increments. The declared protein test elected can be no less than 3 pounds and no more than 4 pounds, in 0.05 increments. Both declared components are subject to the component test ratio between butterfat and protein. The declared butterfat to protein test ratio must be no less than 1.15 and no greater than 1.30, rounded to the nearest five hundredths (0.05). The minimum-maximum component ratios are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

A producer using the Component Pricing option declares test values of butterfat and protein that are necessary to determine the expected total component milk price used to determine expected revenue and coverage. These producer elections using the Component Pricing option are shown in Figure 5. When determining the expected value of butterfat and protein, the average monthly value for each month in the insured quarter is calculated utilizing component futures’ prices and AMS component formulas. The total component price/cwt in Figure 5 represents an expected total component price for Q4 2019 assuming declared butterfat and protein test values of 3.60/3.10, respectively.

Figure 5:

If the component pricing option is elected, a producer’s coverage is based on their declared butterfat test and protein tests. However, to receive your full coverage, your average actual butterfat test and average actual protein test component levels for milk sold during the quarterly insurance period must not be less than 90 percent of the declared butterfat test or declared protein test.

The final butterfat test and final protein test used to calculate the final component pricing milk revenue and the actual component pricing milk revenue for indemnity calculation purposes is determined as follows:

- If either actual component test is less than 90 percent, then, as applicable, the final butterfat test and/or final protein test will be the actual determined test value percent divided by .90. For example, if the declared butterfat test is 5.00 pounds, the policyholder’s average butterfat test during the quarter must equal or exceed 4.50 pounds. If the actual butterfat test is 3.80 pounds, the final butterfat test will be 4.22 pounds (3.80 pounds actual / 0.90).

- For either actual component test that is at least 90 percent of the declared, then, as applicable, the final butterfat test and/or final protein test will equal the declared butterfat test or declared protein test. For example, if the declared protein test is 4.00 pounds, and the policyholder’s average actual protein test during the quarter is 3.80 pounds, the final protein test will be 4.00 pounds.

Premiums will be due in accordance with the initial component calculations; any recalculation of component values will not result in a premium refund.

Farm-Level Factors

Optional Protection Factor:

Under DRP, a producer must elect a protection factor between 1.0 and 1.5, in 5% increments. It designed to provide greater flexibility in matching farm-level production risk. For example, if a producer declares a protection factor of 1.5 and receives an indemnity payout of $20,000, their final quarterly indemnity would equal $30,000, as $30,000 = ($20,000 x 1.5). The producer’s premium increases proportionally along with any indemnity, if one is paid out. Even if there is no indemnity payout, the producer must still pay the premium times their chosen protection factor.

Yield Adjustment Factor:

Each quarter upon the release of state-level milk production data by the USDA via Milk Production reports, a yield adjustment factor will be determined for producers based on actual vs. expected production yields in their state or pooled production regions. This yield adjustment factor is determined by dividing actual quarterly milk production per cow by the expected milk production per cow for that quarter. Both the expected and actual values represent a state or pooled production region yield data, not expected or actual yield for an individual operation.

For example, if expected milk production per cow for a given quarter and state is 7,500 pounds and the USDA publishes actual milk production per cow of 7,800 pounds for that quarter and state, the yield adjustment factor would be equal to 1.04, as 1.04 = (7,800 ÷ 7,500). Similarly, if actual quarterly milk production per cow was 7,200 pounds, the yield adjustment factor would be 0.96, as 0.96 = (7,200 ÷ 7,500).

From a practical standpoint, if the yield adjustment factor is above 1.0, then actual milk revenue is calculated higher and potentially above the threshold that would trigger an indemnity payment. Conversely, if the yield adjustment factor is below 1.0, then actual milk revenue is calculated lower thus reducing the threshold for triggering an indemnity payment.

This holds true regardless of actual farm level production. In other words, the dairy’s actual production may be lower in a given quarter due to farm-level factors while the state or region’s milk production was higher than expected. It may also be true however that the dairy’s production proves larger than anticipated while the state or region’s actual production was lower than expected.

Production Loss Factor:

A dairy producer declares their covered milk production on the quarterly coverage endorsements, but if the dairy does not actually market the covered milk production that was declared by the producer:

- If milk marketings for the quarterly insurance period are at or above 85 percent of the declared covered milk production, then your covered milk production equals your declared covered milk production, even if your milk marketings are lower than the declared covered milk production; or

- If milk marketings during the quarterly insurance period are less than 85 percent of the declared covered milk production, then your total covered milk production for this quarterly insurance period shall equal your milk marketings divided by 85 percent.

For example, two separate quarterly coverage endorsements purchased at different points in time for a single quarterly insurance period, endorsement A has 1,500,000 pounds of declared covered milk production and endorsement B has 500,000 pounds of declared covered milk production for a total of 2,000,000 pounds. The milk marketings are 1,200,000 pounds of milk for the quarter. The total covered milk production for all quarterly coverage endorsements shall be 1,200,000 pounds divided by .85, which equals 1,411,765 pounds.

Premiums will always be due as calculated by your initial declared covered milk production, and they will not reduce because of any recalculations in covered milk production. This is important to understand as even though there is no maximum amount of milk production that can be insured, there is a disincentive to over insure since payments are ultimately determined by actual production, not declared production.

Declared Share:

A producer’s declared share, or actual share, represents the percentage interest in the insured milk as an owner of the dairy operation at the time of the quarterly coverage endorsement. The premium paid and indemnity received adjust proportionally with the declared share of a producer.

For example, if a producer owns 50% of the quarterly coverage endorsement under the DRP program, they only have to pay 50% of any premium costs, but will only receive 50% of any indemnity payouts.

DRP Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

The USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA) has released a FAQ sheet to answer any additional questions that individual producers may have regarding Dairy Revenue Protection, which can be found online at:

https://www.rma.usda.gov/help/faq/dairyrevenueprotection.html

Conclusion

Dairy Revenue Protection represents a new opportunity for producers to address the very realistic risk of a significant and unexpected decline of future revenues and overall profitability. CIH embraces any new tool that offers the dairy industry an ability to protect against declining milk revenues and enhance overall profitability. Protecting revenue at a government-subsidized rate is especially attractive in low margin environments, particularly when premium costs are not due until the end of the period being covered. It is critical to assess how farm-level factors and features under DRP relate to your specific operation. CIH will work alongside your operation to create an integrated margin management policy that ensures you are properly hedged and able to take advantage of greater revenue opportunities if offered above the minimum level of your DRP. We encourage you to learn how a combination of risk management strategies can help you protect and enhance forward revenues and, ultimately, overall profit margins for your dairy operation.

For any questions or to learn how this may specifically affect your dairy, contact CIH at 866-299-9333.

One of the main economic functions of the futures market is price discovery. Participants from all over the world place bids and make offers in a dynamic auction to determine the value of a commodity or financial instrument at any given point in time. Because multiple contracts trade simultaneously for the same commodity in different time periods, both nearby as well as in deferred months and years, this price discovery process is multi-dimensional. It not only reveals the current or “spot” value but also expectations about how that value will change over time. Studying this relationship, referred to as the forward curve, can provide valuable information on how market participants anticipate future price movements for the cash market. It also can help hedgers refine position structure to protect risk in deferred time periods.

The Cash and Futures Relationship

Futures contracts are called derivatives because they derive their value from the underlying cash market. Based on the contract specifications, futures either settle to the cash market through physical delivery as is the case with contracts like corn, or are cash settled where their final value at expiration is determined by some sort of an index as is the case with hogs. In either case, prior to a contract’s expiration and convergence with the cash market, there is a difference in value between the spot cash price and the nearby futures price. This difference, or basis, changes over time where in some cases the cash price may be at a premium to futures, and in others a discount.

Looking beyond the nearby futures contract, deferred futures also may be trading at premiums or discounts to the cash market as well as to nearby futures. One of the reasons why deferred futures prices may trade at a premium to spot prices could be seasonality. For many commodities, there is a normal tendency for prices at certain times of the year to be higher or lower than other times of the year, and the futures curve reflects those seasonal tendencies. Another reason may be fundamental. As an example, there may be a shortage of the commodity in the spot market although the pipeline might suggest ample supply in a deferred period. In such a case, the spot or cash price would be trading at a premium to forward futures prices.

The Hog Market

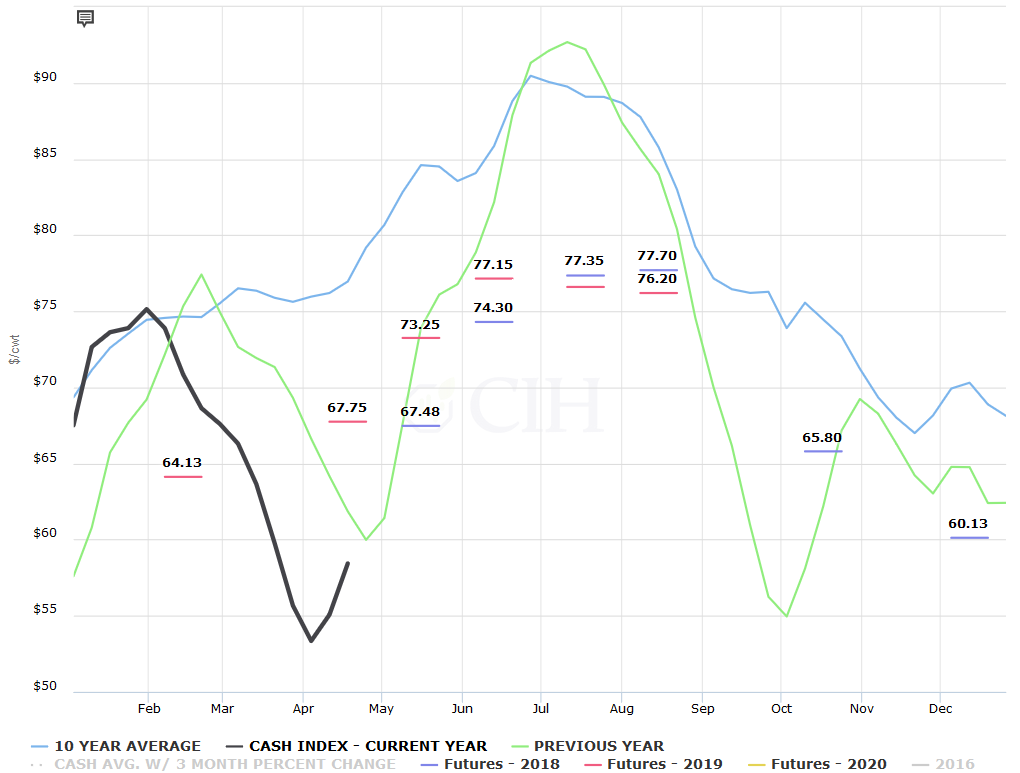

The current structure of the hog market offers one example of the relationship between cash prices and the forward futures curve. Notwithstanding a recent recovery, the cash hog market has been under heavy pressure since late January as supplies have been larger than expected. After starting the year at prices very close to the average of the past 10 years, the CME Lean Hog index declined almost $22/cwt. between late January and early April as hog slaughter and pork production have posted strong year over year increases from 2017 (see Figure 1). Total hog slaughter during Q1 was 31.075 million head, up 3% from a year ago; however, pork production of 6.645 billion pounds during the quarter was 3.7% higher than last year as hogs are coming to market at heavier weights.

Moreover, the latest USDA Hogs and Pigs report indicated that supply growth is likely to continue through the summer and into fall. The hog breeding herd on March 1 was estimated at 6.2 million head, the largest since 2008 with producers reporting that they intend to farrow more sows than a year ago for the next two quarters. March-May farrowing intentions were up 2.1% from 2017 while the June-August quarter showed an increase of 1.4% from last year. Recent news of China’s decision to impose retaliatory tariffs on U.S. pork imports hasn’t been helpful either as much of the offal goes to that market with limited opportunities for other outlets.

Looking at Figure 1, you will notice that the loss in value in the CME Cash Hog Index and subsequent recovery was very similar to last year (green line) albeit around 3 weeks early in 2018. You will also notice the hash marks spread across the page, which represent futures prices as of April 26. The blue lines correspond to 2018 futures while the red lines are the values for futures in 2019. Each value is displayed in the middle of the month when the futures contract expires. The 67.48 value in blue between the month of May and June represents the current value of May 2018 futures which is where the black line is headed over the next few weeks. Given the two values have to converge at expiration, this means that either the black line (spot cash market) needs to rise further, and/or the price of May futures needs to come down in order for the two to converge by mid-May.

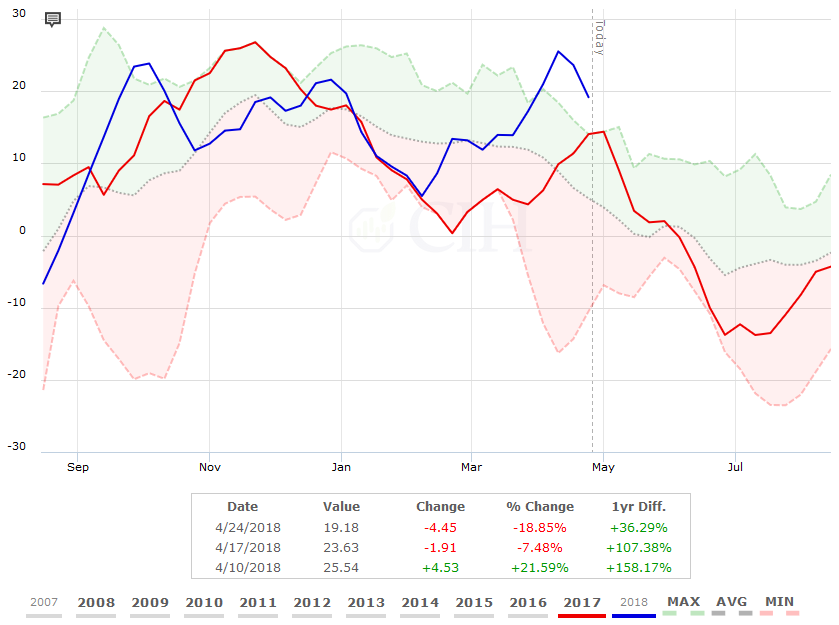

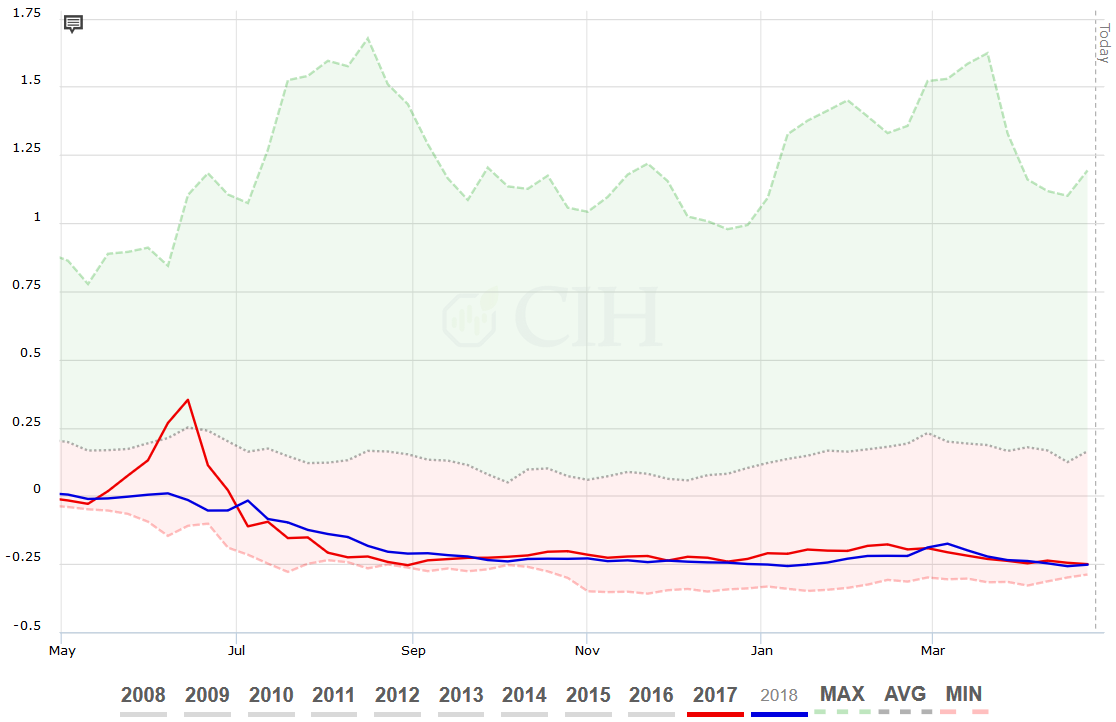

The summer futures prices with June at 74.30, July at 77.35, and August at 77.70 indicate expectations for a continued rise in the cash market or CME Lean Hog Index over the next few months as would seasonally be expected, although those expectations are much more muted than the increase in cash prices we witnessed last year when looking at the green line. This likely is due to the factors previously mentioned with larger hog slaughter and pork production relative to last year and increased trade uncertainties. From a hedging perspective, while the futures market represents a fair estimate of value for summer hogs based on what is currently known, it may make sense for a producer to retain upside flexibility on their price hedges in case the cash hog market is stronger over the next few months. As a counterpoint however, it should be noted that August Lean Hog futures are also currently trading at their highest premium relative to the CME Lean Hog Index in the past decade (see Figure 2).

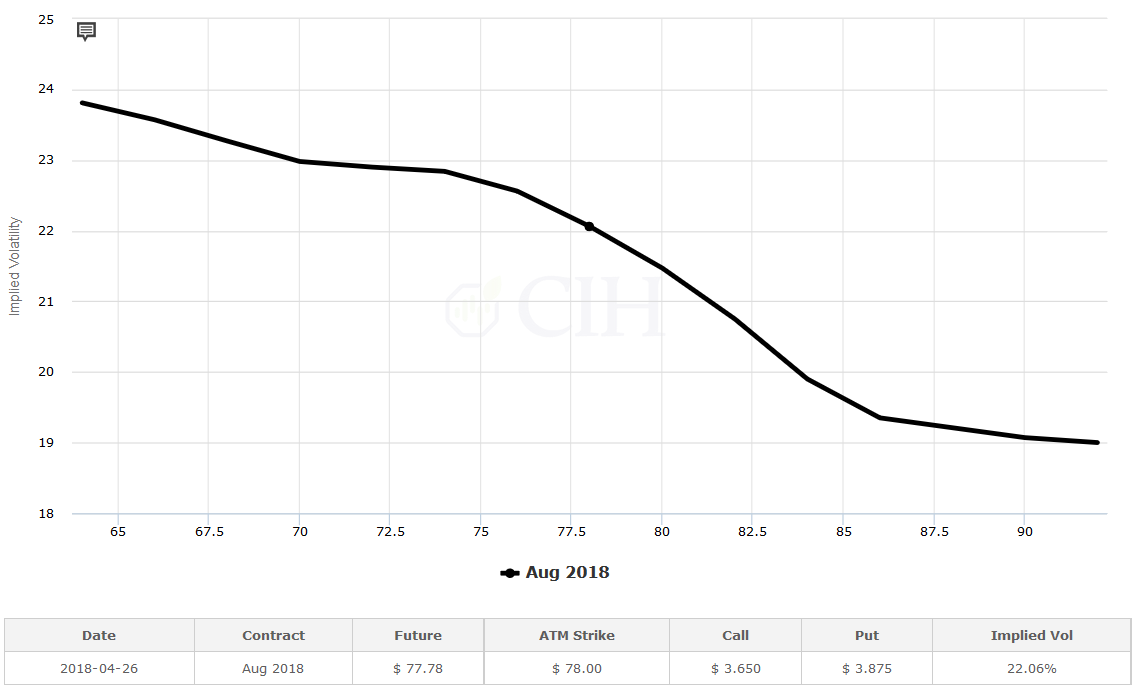

An example of how a producer might address both of these considerations in a hedge would be adding long call options to a short futures hedge or cash sale in the local market against their summer marketings. The August futures are trading around 77.70, so the producer might purchase a call option with an $80 or $82 strike price to address the opportunity cost in a higher market against pre-existing sales either in the cash market or on the board. They may even choose to offset part of the cost of purchasing the call by selling put options below the market. This not only would lower the cost of adding upside flexibility to the hedge, but also take advantage of the current option volatility skew in the market as higher strike calls are trading at lower implied volatilities relative to lower strike puts (see Figure 3).

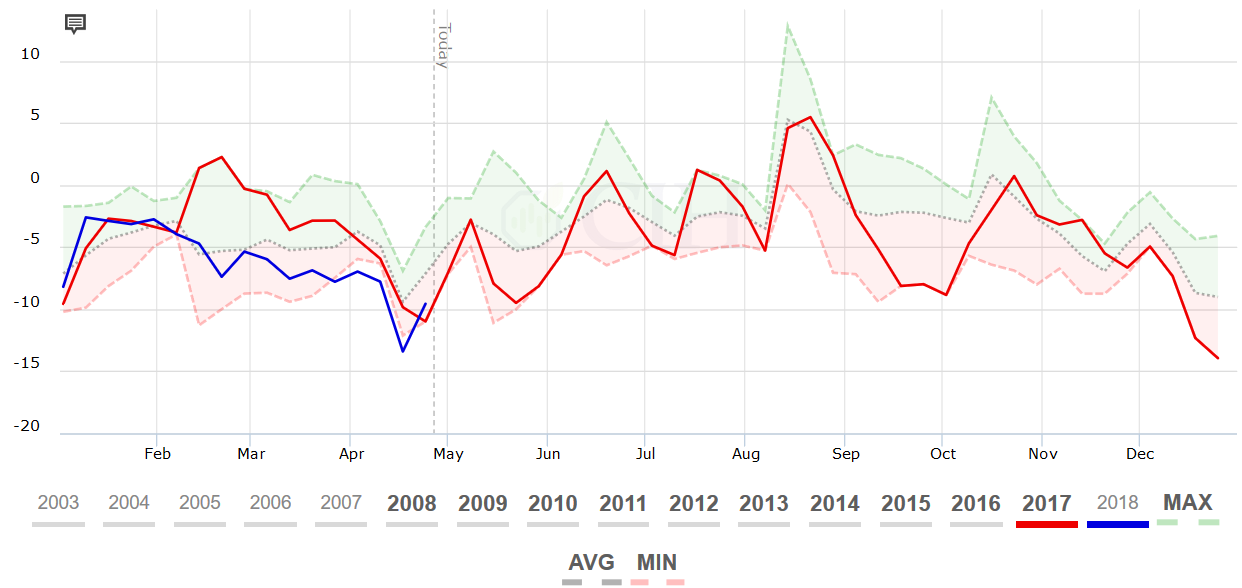

Another consideration for a hog producer from a hedging perspective concerns cash basis levels. With the cash market trading at a discount to futures, hog basis is currently negative and has actually been running at or near new 10-year lows through the month of April (see Figure 4). Because of this, a producer would only want to deliver hogs against the minimum amount necessary to meet packer commitments, and possibly even slow down hedge removals against their marketing schedule.

The Cattle Market

By contrast, the forward curve in cattle offers a different perspective on the relationship between cash and futures prices as well as the implication for hedgers. Unlike the hog market where cash prices are currently trading at a discount to futures, spot cattle prices in the cash market are at a premium to the forward curve. Despite the fact that the number of cattle on feed as a percentage of the previous year has consistently run 107%-109% over the past several months, much of the cattle placed into feedlots last fall were lighter weight animals that require more days on feed to reach market weight. As a result, cattle marketings and slaughter have not kept up with demand as packers have large commitments they need to fill in the spot market.

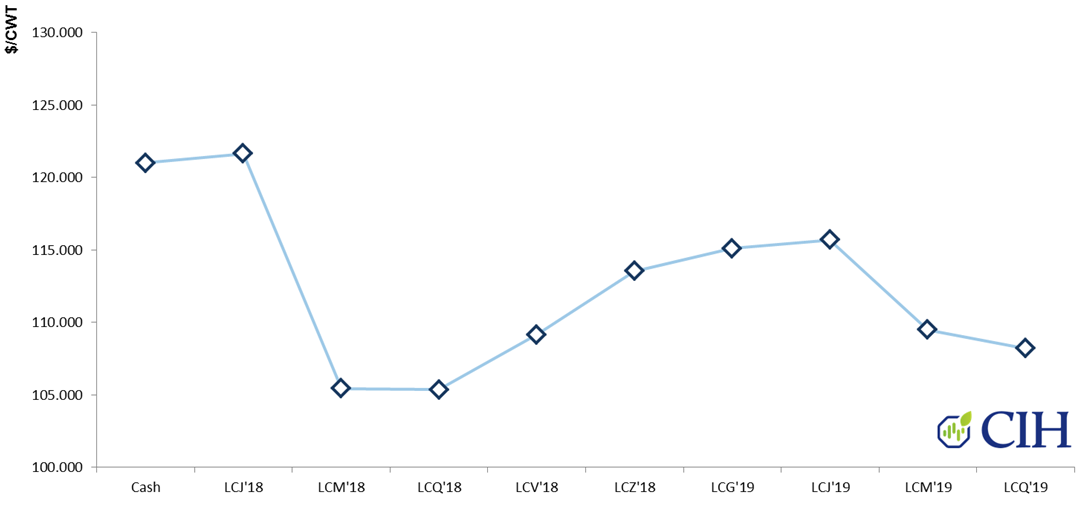

Because of the heavier placements over the past several months however, expectations are that an abundant supply of cattle will be available to the market during the summer marketing period. Since market participants anticipate this increased supply of cattle and beef production over the next several months, the forward curve reflects these expectations with lower prices for summer contracts relative to the spot spring period. Prices are gradually expected to increase heading into the fall and winter from a summer low against the June and August contracts. Figure 5 shows the forward cattle curve out through August, 2019:

Compared to the hog market, the relationship between cash cattle and forward futures implies a much different scenario for cattle producers in managing their inventory and hedge positions. Unlike hogs, the basis has been strong for cattle. Figure 6 displays the current cash basis for live cattle in the Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico region, which has been running at or near 10-year highs over the past month. The historically strong cash basis which is well above average provides a strong incentive for producers to market early and pull supplies forward, hopefully alleviating the possibility of excess supply later in the summer.

Meanwhile, because the forward curve is discounted relative to spot futures and the cash market, a cattle feeder would also be encouraged to maintain upside flexibility in their hedges against summer marketings. Similar to hogs, a cattle feeder might likewise consider adding long call options to a short futures position. Alternatively, they may choose to protect downside price risk on their physical inventory by simply purchasing put options. Depending on their projected breakeven levels, they could finance the purchase of puts by selling upside calls to establish a maximum price on a portion of their inventory.

The Corn Market

Another example of the relationship between the cash market and the forward futures curve is the corn market. After harvesting another bumper crop last fall on record yields that maintained corn stocks at historically high levels, cash corn prices have been depressed with limited expectations for much of a recovery. Recent drought conditions in Argentina however and lower than expected intended acreage revealed in USDA’s Prospective Plantings report has put some risk premium back into the market. In addition, cold and wet weather which has extended through April across much of the Northern Corn Belt has delayed planting progress and likewise added a risk premium to the futures market.

Unlike hogs or cattle, corn is a storable commodity and the relationship between prices of futures contracts on the forward curve typically reflects a “cost of carry” or storage between delivery months. In a situation like the present where supplies are plentiful, there will be a positive carry such that deferred futures are trading at a premium to nearby futures, reflecting the cost of storing the crop between expirations. In a case where there is a shortage, such as in a drought like the 2012-13 crop year, there will be a negative carry or a premium on nearby futures relative to deferred futures contracts. This provides a disincentive for producers to hold on to their crop as they effectively lose money storing between expirations. Figure 7 displays the current forward curve for corn:

For a corn producer, the forward curve on corn implies different considerations for managing hedge positions between old-crop corn in the bin and new-crop corn which is now being planted. Looking at the first half of the curve representing the 2017-18 old-crop marketing year, there is a positive carry as previously mentioned. In other words, the producer is incentivized to hold on to their crop in order to capture the carry in the market. Assuming the producer has storage, they therefore would want to maintain a short hedge in the deferred July or even September futures contract against their physical inventory, representing the horizon of the old-crop price curve.

Another way of looking at this would be to analyze the spread between old-crop and new-crop corn within a historical context. Figure 8 shows the spread between the spot May Corn futures contract and the new-crop December futures contract. You will notice that the 25-cent discount of May relative to December is the same as last year and near a 10-year low for this time of year.

Looking out to new-crop however, the forward curve is telling us something different. Given the previously mentioned dynamics of lower intended acreage and delayed planting progress that has been compounded by the crop losses in Argentina, the second half of the forward curve starting with the new-crop December contract is relatively flat. This is because a majority of the open interest or price discovery in new-crop corn is in the December futures contract, which has been bid relative to the forward contracts on the curve. While the March, May, and July 2019 futures contracts are trading at successive premiums to December 2018 futures, these premiums are relatively small from a historical perspective.

If we look at a similar chart to Figure 8 which now compares the December 2018 futures price relative to the July 2019 futures price, you will notice in Figure 9 that the 16 cent discount of December futures relative to July for new-crop corn is at a 10-year high for this point in the season. As a result, unlike in old-crop where a corn producer would be incentivized to place their short hedge as far out as possible on the curve; in new-crop, there is an incentive to keep the short hedge on the front end of the curve in the December contract, and wait for more carry to be built into new-crop spreads.

The forward curve is an important component of the price discovery process in the futures market and provides valuable information for a risk manager to consider when evaluating their exposure. Understanding the relationship between cash and futures can help producers better manage their hedge positions and leverage the information being provided by the market to take advantage of opportunities that may present themselves.

There is a risk of loss in futures trading. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) publishes a weekly report which breaks down the total open interest as of each Tuesday’s settlement for markets in which 20 or more traders hold positions equal to or above reporting thresholds established by the Commission. The reports are released every Friday and provide market participants insight on how open interest is distributed among different groups of traders. In a very general sense, it breaks open interest down into two categories – reportable versus non-reportable positions – but other classifications have been distinguished by the CFTC to provide further insight on the participation of different type of traders in the market.

History and Breakdown of the Reports

Antecedents of the Commitments of Traders (COT) reports can be traced all the way back to 1924 when the USDA’s Grain Futures Administration, the predecessor to the USDA’s Commodity Exchange Authority and later the CFTC, published its first comprehensive annual report of hedging and speculation in regulated futures markets. Beginning in 1962, the reports were published monthly followed by a mid-month and month-end version in 1990, then every two weeks in 1992, and finally a weekly format in 2000. The data is also now compiled and released on a more timely basis, and has since moved from a fee-based subscription to becoming freely available on the CFTC’s website at the following link: https://www.cftc.gov/MarketReports/CommitmentsofTraders/index.htm

The CFTC collects position data from reporting firms including clearing members, futures commission merchants (FCM’S), foreign brokers and exchanges. While the position data is collected by these various reporting firms, the actual category or classification of traders’ predominant business purpose is self-reported by the individual traders on the CFTC’s Form 40 which is reviewed by commission staff for reasonableness and accuracy. Traders are able to report business purpose by commodity, and therefore may be classified differently for one market versus another.

There are four reports, including legacy, supplemental, disaggregated, and traders in financial futures. The legacy reports are broken down by exchange and include a futures only and a combined futures and options report. Legacy reports break down the open interest into two categories – non-commercial and commercial traders. Supplemental reports break down the reportable open interest into three trader classifications: non-commercial, commercial and index traders. The index trader classification was added in 2007 to provide the marketplace with more transparency on positions in exchange-traded markets, with further classifications subsequently added with the disaggregated report in 2009.

The disaggregated report increased transparency by separating traders into the following four reportable categories: Producer/Merchant/Processor/User, Swap Dealers, Managed Money, and Other Reportable. This development evolved from confusion over what types of traders were holding various positions in the markets. Generally speaking, the legacy form of the report which only defines two categories of traders as commercial or non-commercial were historically seen as hedgers and speculators, respectively. Traditionally, these participants were viewed as those whose positions were tied directly to the physical commodity versus those who had a purely financial interest in the market.

It became clear over time however that there was a need for further distinction. Commodity index fund trading which grew substantially in the early part of the century brought about the initial need for added transparency as these entities held long-only positions in the futures market to replicate holding commodities as an asset class. With large reportable positions, they defined themselves as commercial traders given that their trading was considered a hedge against the underperformance of the various portfolio benchmarks as defined in their fund prospectuses.

The rise of swaps in the commodities market likewise provided another catalyst to further clarify the breakdown of open interest in the commodity markets. Financial entities including FCM’s and other market participants have increasingly been offering structured products to clients that mimic or are backed by exchange-traded futures and options. Here too, the purpose of trading for these entities was to hedge the financial commitments they had with their counterparties in a swap agreement, and it became necessary to define this category separately from commercial traders.

Report Data

The CFTC provides the Commitments of Traders data in both a long and short format. The short format displays open interest separately by reportable and non-reportable positions. For reportable positions, additional data is provided for commercial and non-commercial holdings. This shows total long positions, total short positions, spreading positions, changes from the previous report, percent of open interest by category, and numbers of traders by category.

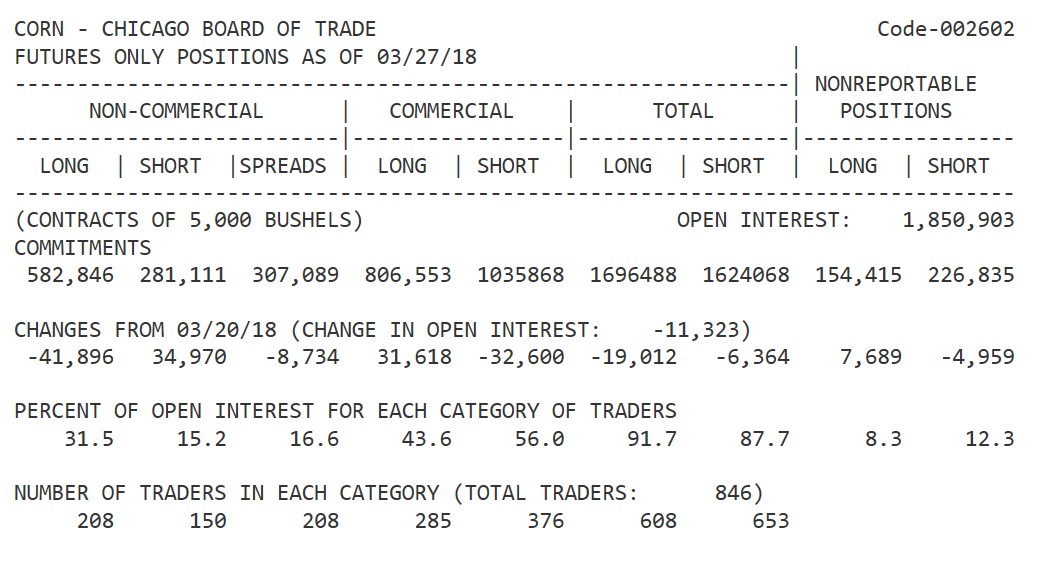

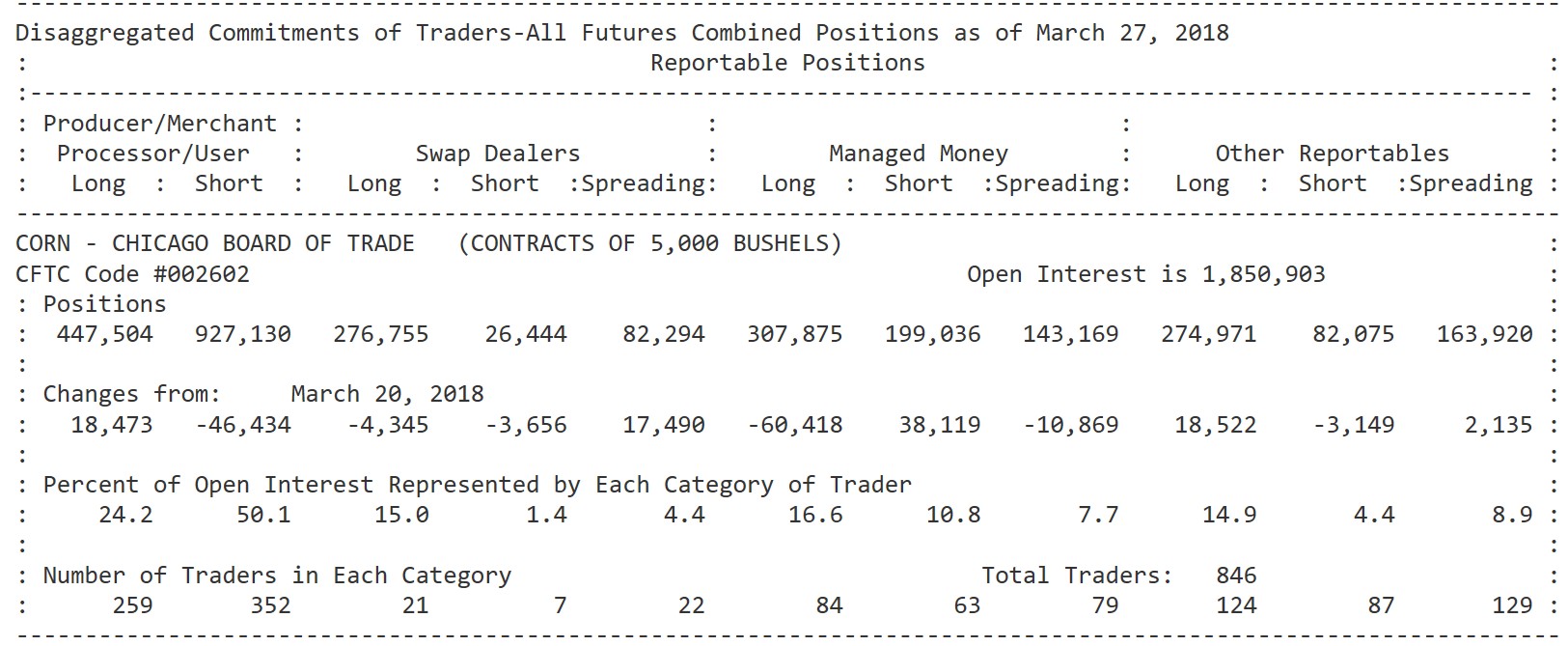

“Spreading” is a computed amount equal to offsetting futures in different calendar months or offsetting futures and options in the same or different calendar months. Any residual long or short position is reported in the long or short column. Inter-market spreads are not considered. The following table shows an example of the short format for the legacy version of the report for CBOT Corn futures and options combined:

The long version of the report also groups the data by crop year, where appropriate as in the case of corn, and shows the concentration of positions held by the largest four and eight traders. The supplemental report is published for futures and options combined in selected agricultural markets and in addition to all of the information in the short format, also shows the positions of index traders. The non-commercial and commercial positions are typically viewed without the impact of the index trader category to analyze changes in positions over time. The reason for this will be explained in the examples to follow under the analyzing the data section.

The disaggregated report evolved from a recommendation to the Commission in September, 2008 to remove or disaggregate swap dealers from the commercial category and create a new swap dealer classification for reporting purposes. In addition, a “money manager” category was also created which for the purpose of this report is a registered commodity trading advisor (CTA); a registered commodity pool operator (CPO); or an unregistered fund identified by the CFTC. These traders are engaged in managing and conducting organized futures trading on behalf of clients. Every other reportable trader that is not identified as a producer/merchant/processor/user, a swap dealer, or a money manager is thus classified in the “other reportables” category. The following table shows an example of the short format for the disaggregated version of the report for CBOT Corn futures and options combined:

Analyzing the Data

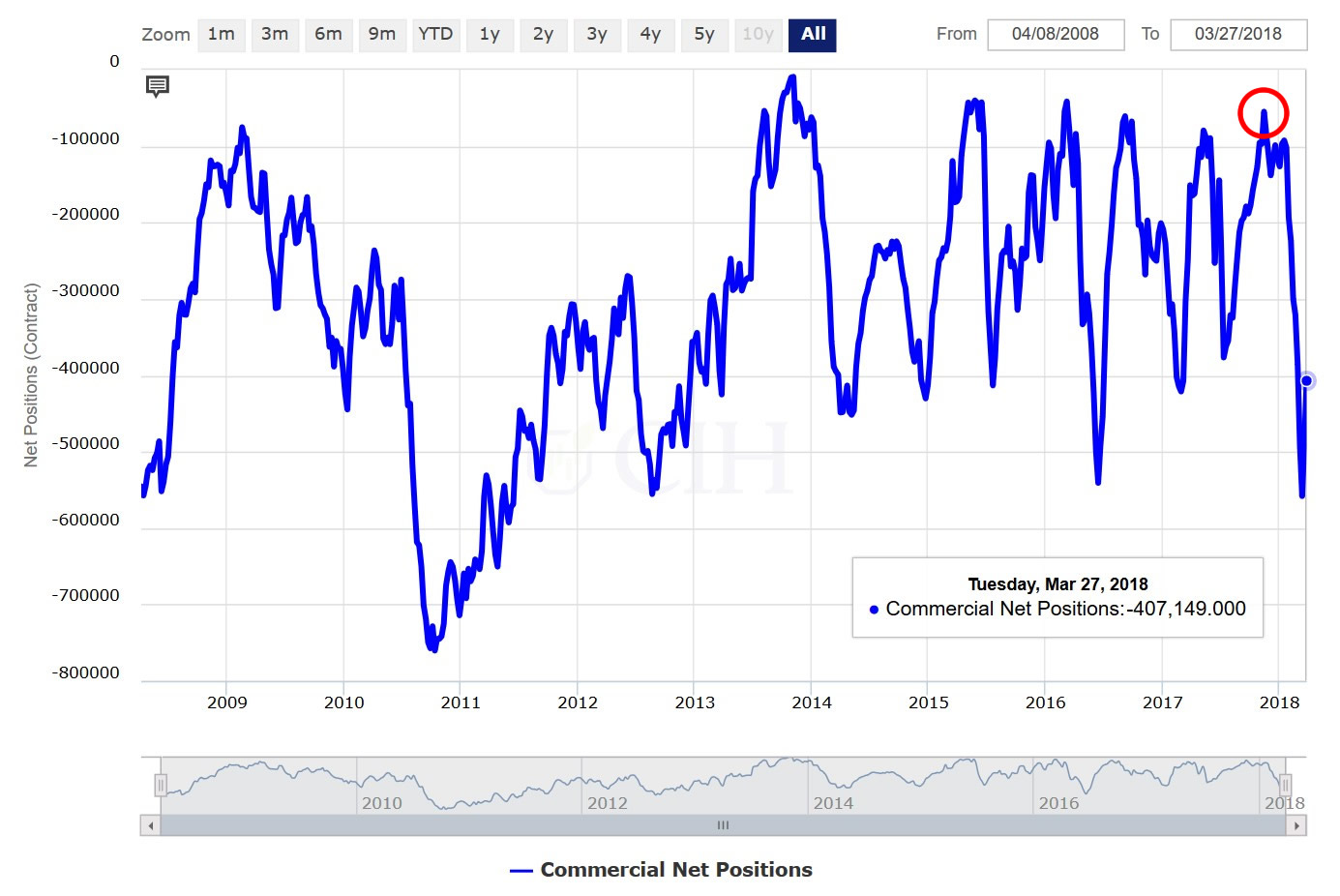

Traders often look at data in the COT reports for clues on market direction and use it as an indicator of potential changes in price trends. Just as with any indicator, there are limitations to using the data as a technical trading tool; however, careful scrutiny of the reports can provide valuable insight when used in conjunction with other market resources. As an example, let’s analyze the recent activity in the corn market. Going back to the basics of the data in the legacy reports, there are two main classification of traders – commercial and non-commercial. The commercial trader touches the physical commodity and their positions are hedging against the risk of an adverse change in value on the physical ownership. This group is therefore always net short the market as they are holding positions against long physical in the cash market. The following chart shows 10 years of history for the net commercial corn position:

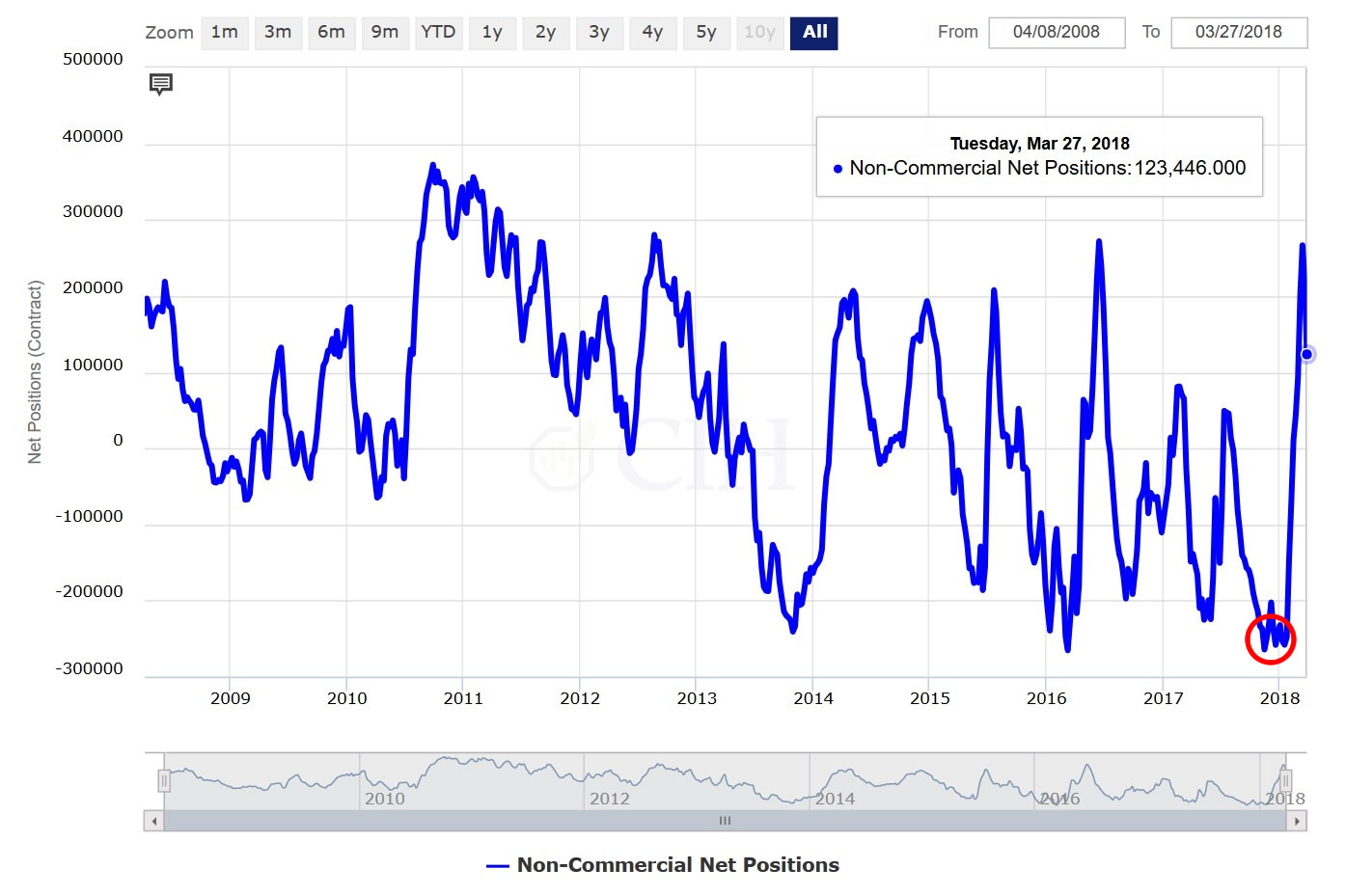

Conversely, the non-commercial trader does not touch the physical commodity and is not hedging risk of adverse price movement in the cash market, although this collective group of traders may be either net long or net short the market depending on their price bias and market outlook. While the legacy report historically has not considered the impact of index traders on this category of open interest, it is possible to separate out the Commodity Index Trader position when analyzing the data based on the supplemental report that has been in use for over 10 years now. Because the CIT position is always net long (see chart below), this provides us with a more accurate view of the non-commercial net position.

Since the CIT is mostly a passive, long-only market participant, if we look at the non-commercial net position without this component, we get a better picture of the speculative participation in the market:

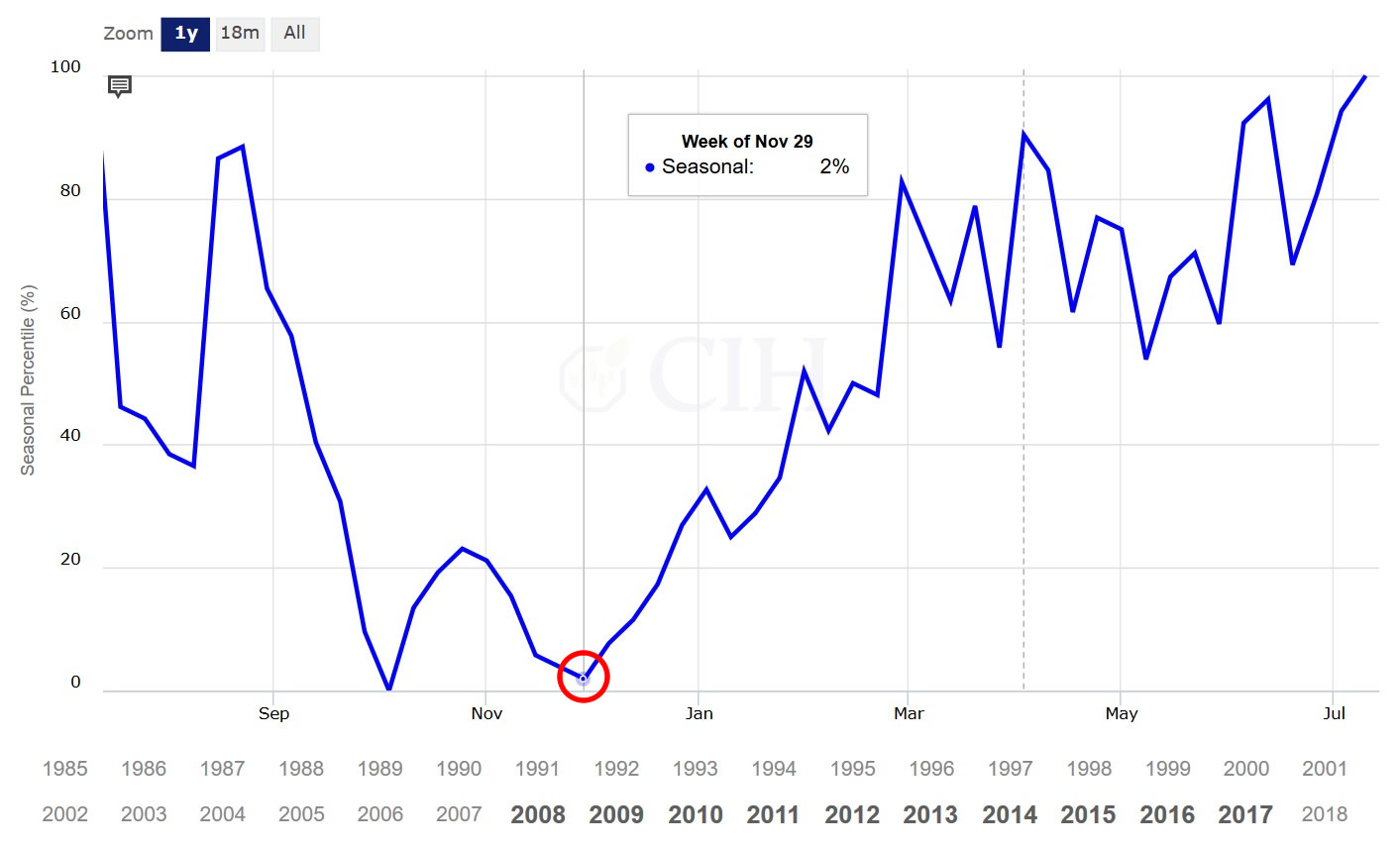

Notice in the commercial and non-commercial charts above, there are two highlighted areas of interest represented by the red circles. Each of them corresponds to a roughly two-month period between mid-November and mid-January when there was a historical divergence between the two data series. The net commercial short position was nearly the smallest of the previous 10 years at the same time that the net non-commercial short position was the largest. This divergence between the positions of the two main categories of open interest also was occurring in conjunction with corn futures that were trading at the bottom decile of the previous 10 years of price. Another interesting point to note about the corn market during this period was that the divergence in the COT data was also developing at a time when there historically is a tendency for prices to be at a seasonal low:

While not necessarily a bullish signal in and of itself, the divergence in the COT data late last year did provide a warning sign for a corn market that had been trending down for months and was mired in deep bearish sentiment. With speculative short interest already at a historical extreme, it suggested that there were very few if any incremental sellers left to continue pressuring the market lower. This can also be seen looking at a price chart of corn from that time as the momentum of the downtrend had slowed substantially during Q4:

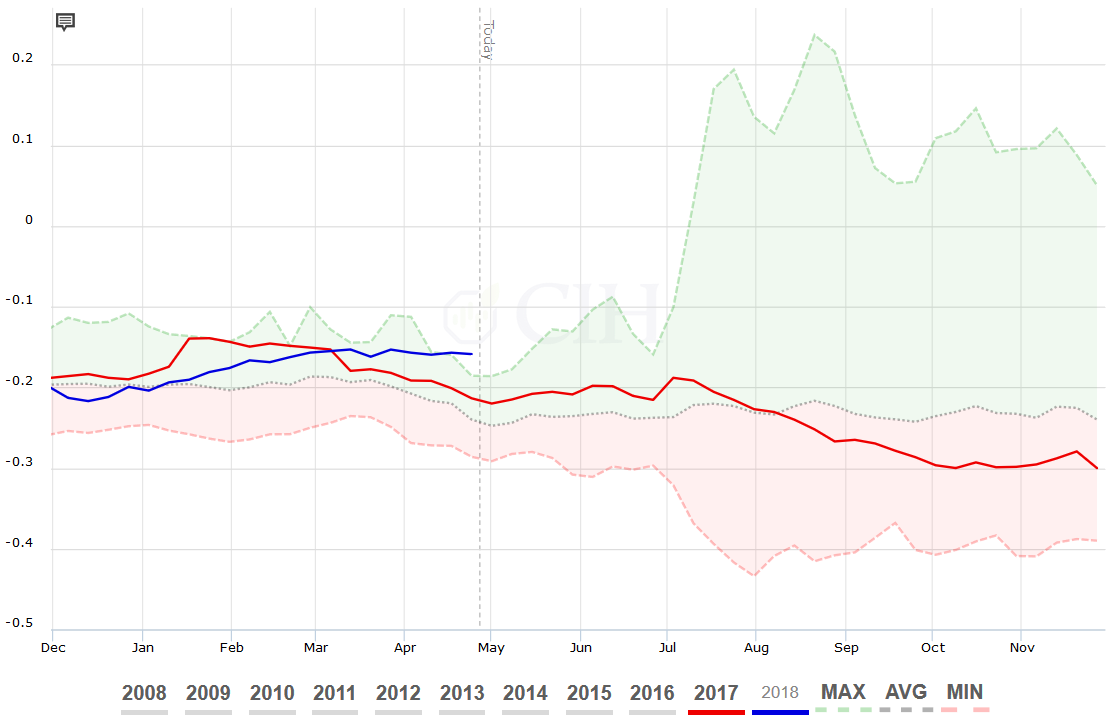

Moreover, if there were some catalyst to begin moving prices higher, as the drought in Argentina subsequently provided, speculative short-covering can quickly fuel an unexpected price advance. While the corn market represents an obvious example with the divergence between commercial and non-commercial net positions at historical extremes, sometimes hints in the CFTC COT data are more subtle. The recent hog market is a good case in point as an example of a bearish divergence. Although the absolute value of the net commercial short position and the net non-commercial long position were not at historical extremes, they were showing a pretty stark divergence seasonally for that time of year based on 10 years of data for early January:

Unlike the corn market example, where prices historically were trading at extreme levels with a seasonal tendency to move in the other direction, the hog market was beginning to flash other warning signs such as weekly slaughter running well ahead of what was implied by the December Hogs and Pigs report. Spot April Lean Hog futures prices have since dropped around $20/cwt. from the highs back in early January:

Although the CFTC Commitments of Traders data by itself does not provide a definitive signal for price direction in any particular market, it nonetheless has value in shedding light on the breakdown of open interest and how positions are distributed across the various participants in the market. It is definitely a resource that should be understood, evaluated, and considered as part of a trader’s decision to initiate and manage positions in the market.

The idea of “saving for a rainy day” traces its roots back to at least the 16th century, but it may as well have originated on an American farm.

Most producers inherently understand that they operate in cyclical industries. These cycles ebb and flow with strong profitability in some years followed by very weak or negative margins in others. Because most producers realize that there will be challenging years in their operations, they know to hold onto profits in a strong year to ride out the weak part of the cycle. For that reason, they may allow their balance sheets to expand in good years with solid margins, and then let the ledger erode during bad times. But leveraging hedging tools to maintain a consistently strong balance sheet may offer a better alternative.

Hidden Value

Some producers mistakenly think that the costs involved with hedging means that active risk management is not worth the effort. In order to remain viable for the long term, they may focus on being the lowest-cost producer, in the hope of simply outlasting their neighbors.

A producer, or their accountant, analyzing hedge performance over several years of active risk management would likely see realized hedging gains in some years offset by losses in others. From a purely numbers perspective, they may reasonably conclude that there was little or no net long-term benefit. This is especially true when one considers the expense of hedging in terms of transaction fees, interest expense, staff time and other costs.

However, while the balances of a hedging account or group of accounts may fluctuate over time with the volatility in the underlying markets, they also help stabilize the balance sheet. In bad years, the operation will likely lose money in the open market on spot purchases and sales, but to the extent these losses are offset by hedging gains in a brokerage account, the balance sheet will not experience the erosion that would otherwise have occurred. The reverse is also true: in very good years, the losses in a brokerage account will not allow the balance sheet to expand as much as it would have otherwise.

This steadying of the balance sheet also helps to improve cash flows. By actively managing forward profit margins, agricultural operations narrow the range of possible outcomes in a given marketing year or period. As an example, let’s say Producer A made $6 million in 2015, then lost $4 million in 2016, resulting in a net outcome for the two-year period of a $2-million gain. Contrast that with Producer B who made just $2 million in 2015, then broke even in 2016. While he ended up with the same $2 million net gain, unlike his counterpart, Producer B maintained a positive cash flow over the two-year period. As a result of that difference, he would likely have been better able to stay current with the operation’s bills.

Benefits of a Steady Balance Sheet

Besides positive cash flow, there can be other benefits to reducing variability in the balance sheet. In consideration of the desire for most operations to remain viable for the long-term, gaining stability and predictability in cash flows can allow a business to confidently make decisions about long-term operational improvements that might require multi-year investments. For example, by expanding or incorporating improved technologies, an operation may be able to gain economies of scale that serve to lower the costs of production.

A bank will most likely have more confidence in lending to an operation with a stable balance sheet and cash flows, making funding easier to facilitate these investments – particularly in down years or negative parts of the cycle when the investments might be less costly. By contrast, operations with eroding balance sheets may forgo investing in their businesses. Restricted cash flow may also lead to strained relationships with lenders and input suppliers.

Reducing variability in earnings and cash flows will also assist in transitioning the business to the next generation through succession planning. In addition, the business will be less likely to fail if the balance sheet is more stable from year to year. Perhaps most of all, a strong balance sheet helps empower you to achieve your long-term vision for your operation.

If you would like to learn more about how you can keep your balance sheets strong throughout the year, please call CIH at 1.866.299.9333.

Although it is easier to strategize about protecting profitability when times are good, a sound risk management plan applies to all margin environments, and is especially important when the outlook is bad. When margins are low and opportunities are hard to find, producers may not consider it worthwhile to initiate margin coverage and may prefer to stay open to the market. While understandable, that tactic leaves operations vulnerable to further margin deterioration. For instance, many operations may now be in the situation where they don’t have adequate coverage in place for the current margin outlook because profitability projections over the past several marketing periods never presented a catalyst to trigger a risk management decision.

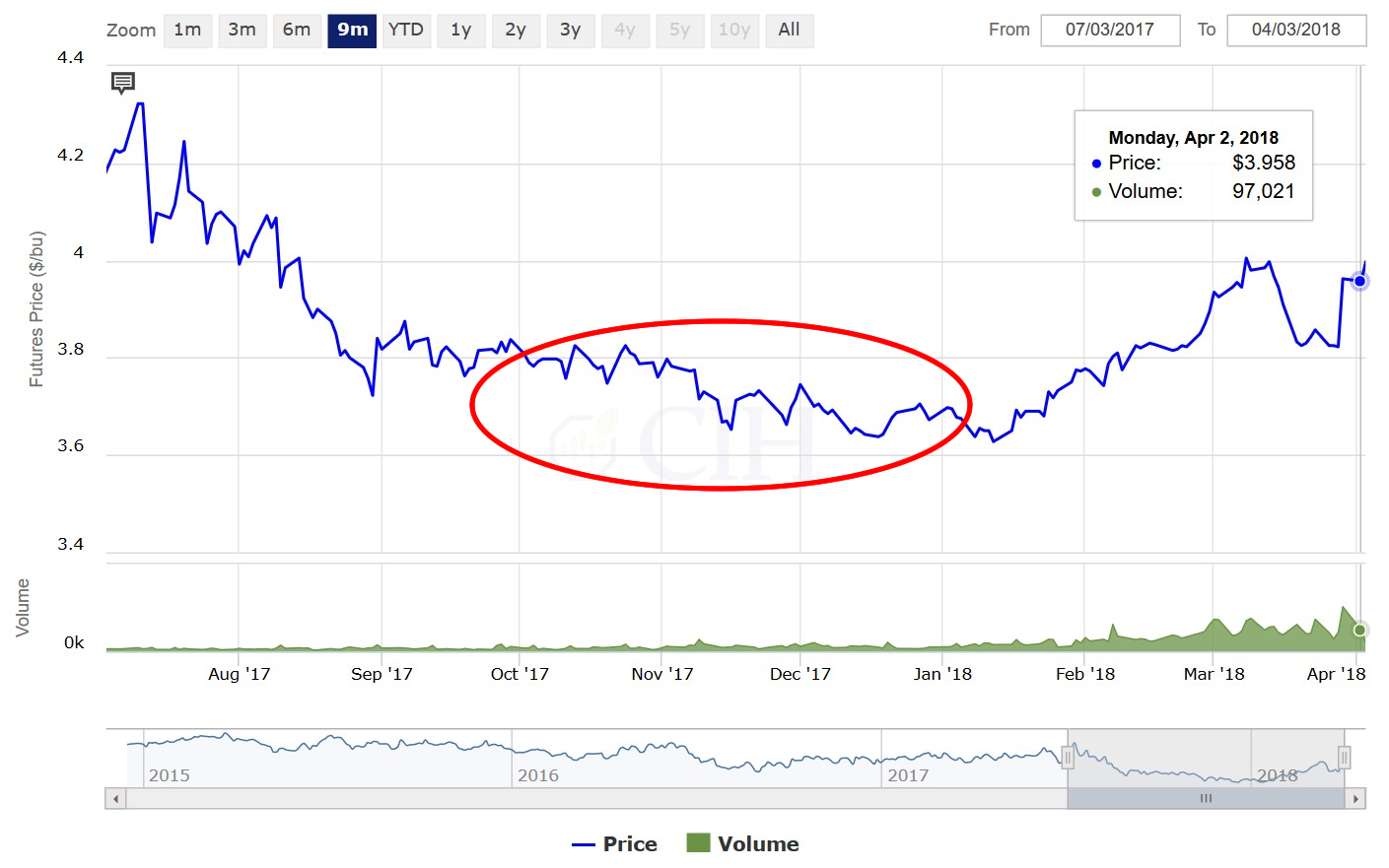

As an example, a crop producer may have set targets this past growing season to establish sales on expected production. Looking at CBOT December Corn futures, the producer may have picked $4.00/bushel as their first target to initiate sales, with a plan to scale up commitments in 10-cent increments. But unless the producer had started managing margins well in advance of this year’s marketing period, that plan would have led to only a couple of sales by early July, when the price reached $4.17. But after mid-summer, the price of corn proceeded to decline steadily and offered no further opportunities to capture attractive margins. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: December 2017 Corn Futures (Year-to-Date)

Contingency Planning

The example of the crop producer’s marketing plan is a common one and may be thought of as “Plan A.” In a best-case scenario, the market will cooperate and allow the producer to scale into selling targets at incrementally higher prices, thus establishing favorable margins over time if all of their planned targets are triggered. A hog or dairy producer likewise may select thresholds of historical profitability to initiate strategies to protect forward margins, though these also rely on the market cooperating and delivering those opportunities such that the margin coverage is established.

While having Plan A is a good starting point for a sound margin management policy, all risk managers also need a Plan B. This plan addresses the possibility that the preferred course of action can’t be executed due to unfavorable market dynamics. While contingency planning is not exactly fun and no one wants to think about what they will do when things go wrong, a thoughtfully crafted backup plan can provide many benefits.

A good starting point for a backup plan might be addressing catastrophic risk. As an example, a producer could look at their margin history and determine some threshold level where they would absolutely want to have protection against a worst-case scenario. In the current environment where many producers are either at, or slightly below, breakeven levels, they might start by considering their cash flow situation. They could work with their lender to determine at what point they would no longer be able to afford a loss exceeding “x” amount of money for “y” period of time before things became problematic financially with their loan covenants. This could help to define that line in the sand.

As an example, following a $2.00/cwt. drop in the price of milk futures from earlier this summer, a dairy producer might opt to purchase out-of-the-money put options in deferred months to protect their revenue from any further declines. This strategy would help to mitigate catastrophic losses in the case of a market that moved sharply lower. A crop producer might likewise choose to purchase put options on deferred corn, soybean and wheat contracts for unpriced inventory they have in storage from this past year’s harvest.

One important component of this type of planning though is determining when to pull the trigger. Ideally, it would be best to wait for the market to provide opportunities to execute Plan A. While a producer is waiting however, it is necessary to consider whether that plan may need to be adjusted. A football analogy might be a quarterback calling an audible at the line of scrimmage because they don’t like the defensive setup against the play that was planned to be executed. This is when Plan B comes into play.

The producer may determine ahead of time, based on some sort of secondary trigger, when they will proceed with implementing their backup plan if their primary one can’t be executed. One example of this might be the dairy producer deciding that they won’t let their projected margins drop below a loss of $0.50/cwt. before deciding to act and purchase the defensive put options against their forward milk revenue.

Another example might be the crop producer choosing a point in time during the growing season, such as early to mid-summer, as a seasonal threshold to establish protection. The benefit in both cases is that the producer will know ahead of time that they will have some protection in place, regardless of how the market unfolds. This will also help to assure that a catastrophic event with extremely negative margins is avoided before it becomes a problem that needs to be managed under duress.

Be Ready to Adjust

A contingency plan is meant to address a worst-case scenario, but ideally the margin profile improves over time. If a producer is implementing Plan B, there should also be a corresponding strategy to adjust their position and protection to capture better margins. In the previous example, the dairy producer may purchase out-of-the money puts on milk to protect the catastrophic risk of prices declining further; however, they should also incorporate into that plan a strategy for capturing any improvement in forward margins in a recovering market.

For instance, if the dairy is purchasing Class III Milk put options at the 14.50 strike price, they might set up an alert to be notified if milk prices rise above a certain target price, such as 15.50/cwt. In this scenario, they could opt to roll their put options up to a higher strike price, and possibly pay for this increased cost by selling call options. Alternatively, they may simply decide to execute fixed sales if they are projecting a profit margin they consider acceptable for the operation.

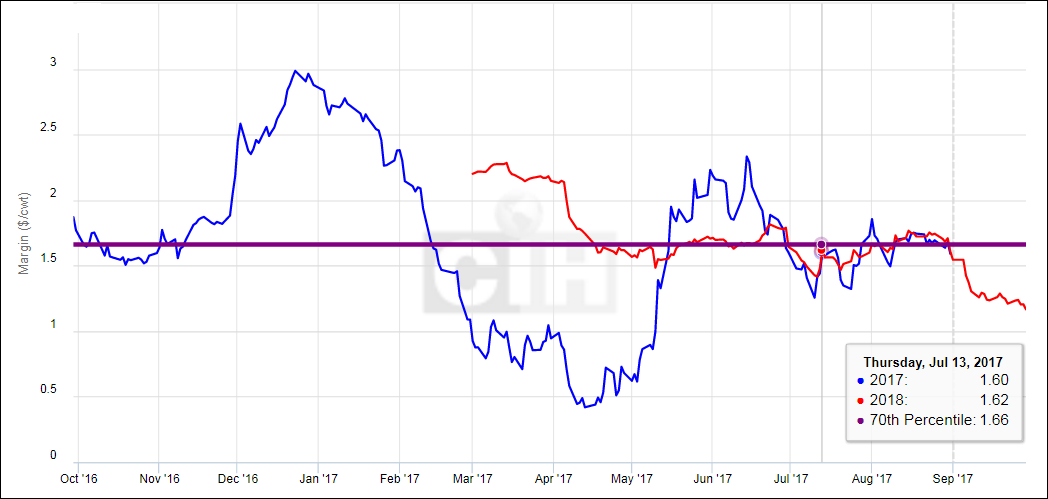

To illustrate this example, consider a hog operation that was monitoring their risk on forward production looking at Q1. There has been much discussion recently about hog slaughter weights increasing and the possibility of larger supplies coming to market that may be getting backed up on farms. There is also concern about prospects for forward demand given intense competition from competing proteins. While projected forward Q1 margins have improved recently and are currently above the 80th percentile of the previous 10 years, they have mostly existed below breakeven until earlier this fall (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Q1 2018 Hog Margin

While many operations took advantage of the strengthening margins during the month of October to scale into Q1 coverage, some became concerned as margins deteriorated into early November due to the aforementioned market dynamics. With perhaps no more than 50% coverage in place against Q1 amidst a questionable outlook, some operations may have chosen to implement a Plan B strategy in mid-November to increase coverage and offset more risk. With projected margins around $1.50/cwt. on November 17 and April Hog futures trading at $71.00/cwt., a hog producer may have opted to purchase a slightly out-of-the-money put option at the $68 strike price for a cost of around $2.50/cwt.

While the worst-case scenario in this example would equate to a loss on that portion of their production in a falling market, it would nonetheless be a defined loss and mitigated to some degree by the portion of the production that was protected at stronger margins. This may also have helped the producer in year-end discussions with their lender feel better about cash flow projections, particularly given that most operations are currently faced with negative spot margins in Q4.

As it turns out, hog prices and margins have recovered over the second half of November. With April Hog futures recently trading over $75.00, the producer would have been able to take advantage of the increase in price by strengthening their protection. For instance, they may have set an alert to trigger an adjustment if Q1 margins got back above, say, the 80th percentile, which they did recently on November 28.

As an example, they could have rolled up their floor from $68 to $74, and basically paid for that adjustment by selling the April $80 call option. For a very limited cost of around $0.50/cwt., this would have raised their hog price floor above the cost of production, thus preserving a positive margin on that portion of their risk. It also would have allowed the margin to continue strengthening above the 90th percentile before the operation would be obligated to a sale on that portion of their hogs.

Some other producers may have opted to simply liquidate their $68 puts, realizing a loss of around $1.00/cwt. against a fixed sale of futures or a commitment in the cash market with their packer. Regardless of how they may have reacted to the recent increase in hog prices and strengthening margins, it is important to have a plan in place to adjust Plan B protection into Plan A.

If you have questions or would like to discuss how to incorporate contingency planning into your margin management policy, please call 1.866.299.9333.

As both corn futures prices and corn option implied volatility hover near historical lows, livestock producers may want to consider securing low-cost protection now for corn purchases farther out in the future.

New Lows for Corn Option Volatility

After a growing season that was surprisingly better than most analysts expected, the U.S. is projected to harvest 14.28 billion bushels of corn which will allow ending stocks to build for the fifth straight year since the historic drought of 2012. As a result, corn prices are languishing at multi-year lows just above $3.00/bushel, a level that has established itself as a de-facto floor in the post-ethanol era (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Continuous Corn Futures (Oct 2006 – Present)

Given this knowledge, there isn’t an expectation for prices to decline much further, especially considering that we are about halfway through harvest which seasonally marks a low point in futures as well as the cash market. At the same time, there isn’t much of an expectation for prices to rise significantly either with the large stocks overhang and lack of any near-term catalyst to cause longer-term supply concerns. As a result, options on corn are priced accordingly, with expectations for future volatility very muted as we move forward through 2018. As an example, the implied volatility on July 2018 corn options is currently trading at 16%, a new 15-year low for not only this time of year, but at any point during the year (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: July 2018 Corn Implied Volatility vs. 15 Year Range

Risks Remain for Corn Buyers

While there certainly isn’t much on the horizon to jolt the market higher and cause corn to break free from the 15-cent trading range it has been stuck in for the past two months, risks still remain for corn buyers. First, commodity funds now hold 213,806 contracts of short positions in the market, approaching a record level from early 2016 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Commodity Fund Net Corn Position, Jan 1, 2006 – Oct 24, 2017

In addition to the possibility of commodity fund short-covering, there is also the issue of a potential adverse weather development in South America as their growing season gets under way. According to the Rosario Board of Trade, corn planting progress in Argentina is almost 35% delayed compared to last year due to flooding. As of October 13, only 57% of the area had been planted, compared to 92% at this point last year. In addition, almost a million acres are still flooded in the north of Buenos Aires Province and south of Santa Fe. Meanwhile, a lack of rainfall has been a focus in the Midwestern growing region of Brazil. Although it is early in the growing season and there is no immediate concern to crops in either country, these are still risk factors for corn buyers to contend with over the next several months.

Purchase Protection When It’s Cheap

Given these uncertainties and the low historical level of both corn futures prices and corn option implied volatility, it may be prudent for livestock producers and other purchasers to consider longer-term protection for projected purchases through 2018. While some corn buyers may be comfortable simply booking corn in the current market given the historically low price levels, others may be more cautious with deferred purchases. Even though the spot corn price is historically low, the “carry,” or premium, of deferred corn futures prices to spot values is also historically wide. Figure 4 shows that at a current carry of around 30 cents/bushel, the spread between spot December and next year’s July corn futures contracts is near a five-year low and at the 10th percentile of both the past 10 and 15 years. Therefore, a buyer of deferred corn would be paying into this historically wide premium to secure future purchases.

Figure 4: Corn Futures Historical Spread Statistics (Dec 17-July 18)

Because of the historically wide carry and amidst the uncertainty over the future price outlook, corn options may be an attractive way to protect forward purchases and upside risk in the current environment. As an example, let’s say a hypothetical corn buyer has to purchase the equivalent of 100,000 bushels for the months of May and June against July 2018 futures. The July 2018 corn futures contract is currently trading at a price of $3.76 ½, about 30 cents/bushel over the spot December 2017 price. The buyer wishes to protect this price level but at the same time, preserve the opportunity for the price to decline in a falling market. A July 380 call option is trading for a premium of 17 ½ cents/bushel. If the buyer purchases this call option, their maximum price for corn in this purchase period (exclusive of basis) would therefore be $3.97 ½, which is the equivalent of the strike price of the option plus the cost of the premium. Should the market move lower, the buyer will be open to price and effectively 17 ½ cents above the market for their purchase.

While this scenario assumes the option is held until expiration in late June, the buyer will most likely exit the option ahead of expiration following a change in price. Ideally, if the market moves lower, the buyer will be able to purchase the corn cheaper while still retaining some of the residual call option value. Even if the market does not move, this premium will erode very slowly with the passage of time. Figure 5 illustrates the theoretical value of the option about three months from now on February 8. Assuming no change in the corn futures price or in the implied volatility of the option, the July 380 call would still be worth almost 14 cents, thus only losing about three cents of value in the next 98 days.

Figure 5: July 2018 Corn 380 Call at 135 DTE

Now let’s consider another scenario in which there is still 135 days to expiration on February 8, but the implied volatility of the option has risen four points to 20%, about the same level as this year’s implied volatility for July corn options in early February, and still well below average from a historical perspective. Figure 6 shows that the increase in implied volatility in this scenario will give the option a theoretical value of about 17 ½ cents, completely offsetting the time decay of holding the option over the next three months.

Figure 6: July 2018 Corn 380 Call at 135 DTE and 20% Implied Volatility

While the implied volatility of July corn options may also decline between now and February, there is a seasonal tendency for it to gradually increase into the spring (see Figure 7). Thus, a corn call option buyer can leverage a few characteristics of the current market profile to their advantage: the fact that prices are historically low, but the carry is also wide; that corn option implied volatility is trading at a new 15-year low; and that there is a seasonal tendency for this implied volatility to rise over the winter – potentially mitigating the impact of time decay during this holding period. While it may be unlikely for corn prices to rise significantly over the medium term, there remain risk factors in the market and it is not necessarily wise for buyers to be complacent. Call options can help draw a line in the sand against deferred purchases, protect historically low price levels, and preserve opportunities for better pricing opportunities down the road.

Figure 7: July Corn Option Implied Volatility 10-Year Seasonal Tendency

If you’d like more information about how to protect forward corn prices and livestock margins, and how options can help you maintain the flexibility you need to navigate an increasingly uncertain landscape, please call CIH at 1.866.299.9333.

Recently, many dairy producers have seen their revenues decline as a result of mandatory deductions from processing plants. While no one likes a smaller milk check, dairy risk managers who want to protect their profitability will need to account for these deductions as they calculate their forward margins and consider adjusting existing margin management strategies to account for the impact of the deductions.

Balancing Milk Supply

Processing plants balance changes in supply of milk against processing capacity and seasonal demand for end products. Spring flush brings more milk to plants, but plants compensate with longer operating hours or agreements with milk handlers to make sure all milk is processed. But demand for dairy products is seasonal and does not always coincide with spring flush. As school season begins in the fall, fluid milk processors increase production, which pulls milk away from butter/powder plants. But even on a daily basis, regardless of season or supply of milk, plants will buy/sell spot loads to either fill an existing order or reduce excess supply. This is part of the business. But what happens when all processors in a region are at capacity and unable to handle the milk supply? Plants with excess supply are forced to either dump milk or haul it long distances to find a home. Either way, they face additional costs, which are then passed on to cooperative members through deductions to their milk checks, often labeled as “balancing plant costs.”

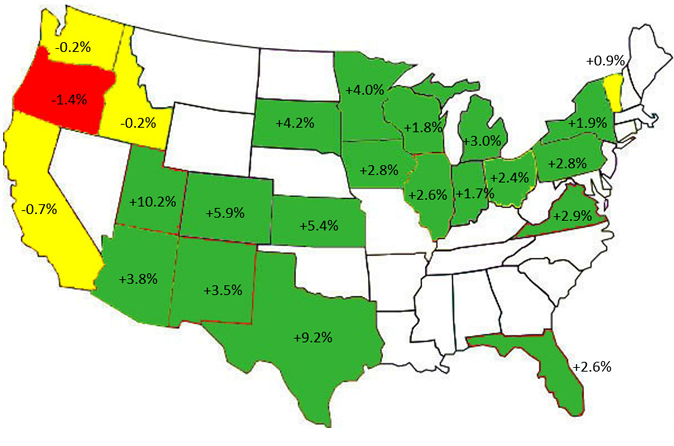

While national year-over-year milk production has been increasing steadily since this past spring, the growth has been uneven; significant growth in the Southwest, Upper Midwest and Mideast Marketing Orders has been offset by lower milk production in California and the Pacific Northwest (See Figure 1).