Much has been written about the negative outlook for the swine industry and the extremely depressed returns producers are currently experiencing. By some measures, this is the worst environment we have seen since 1998 with losses approaching $60/head and negative margins indicated through Q1 next year (Figure 1). There clearly are oversupply issues which are pressuring the pork market, but besides trying to understand why the market is so weak, many producers are also asking what they can do about it.

Figure 1. Iowa State University Historical Hog Production Returns:

Fortunately, many producers have some degree of coverage in place through year-end although likely not as much as they would desire. The increased use of government-sponsored insurance tools to manage hog revenue risk including LRP and LGM have fortunately helped by providing a floor under the market for protection taken earlier in the year when forward margins were profitable. In thinking about this existing coverage, producers should make sure that these hedges are as effective as possible to protect ongoing weakness.

While near term margins are depressed, higher hog values and cheaper feed costs being projected by the forward futures curves offer a bit more optimism for 2024. Game planning to add flexible floors under these deferred margins while allowing for upside participation should be one area of focus (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Q2 2024 Hog Margin with 20-Year Historical Range:

While the forward margin opportunity may not be as compelling as earlier in the year, an argument can still be made that it is worth protecting. Figure 3 details a comparison of the CME Cash Hog Index that the corresponding Lean Hog Futures contract settles against with current futures values for both the remainder of this year and 2024. The solid black line shows the current CME index around $80/cwt. with the nearby June futures contract trading at $77.65/cwt. That hashmark and the black line will converge in mid-June when the futures contract expires.

As you can see from the chart, the forward curve of 2024 futures values are all at or above the 10-year average of the CME Lean Hog Index which may be considered “optimistic” given the current market situation.

Figure 3. CME Cash Hog Index Versus Futures:

Much of the current weakness in the hog market can be attributed to softer demand, but recently supply has been cumbersome as well. An increase in demand may do some of the work, although lower prices are likely going to be needed at retail to move additional pork through domestic channels. There also remains concern that the U.S. economy will slip into recession later this year which is clearly a headwind for domestic demand.

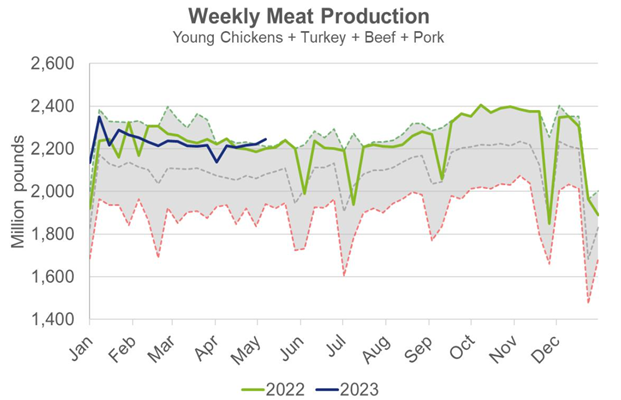

One bright spot so far this year has been export demand and we would expect this to continue as EU production continues to contract. However, domestic demand and meat production continue to offer headwinds. While we are clearly seeing lower beef production this year, the opposite has been true for poultry such that total meat supply for this time of year is sitting at a new 10-year high (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Total U.S. Meat Production Versus 10-Year Range:

Similar profit margin pressure in the poultry sector is beginning to slow production, although a further slowdown will likely be needed in both the poultry and pork sectors which could take time. Also, any move to limit supply by culling more sows historically tends to increase pressure in the short run as more pork is initially added to supply.

Any new coverage that is added for next year should be done with care to ensure that maximum flexibility is allowed to participate in higher prices. LRP and LGM are good alternatives to consider in the current environment given the cash-flow benefits and subsidies relative to exchange-traded options. Also, it might be wise to consider more coverage than would otherwise be executed under normal circumstances where an operation might incrementally chip away at opportunities as margins strengthen.

The hog market may currently be oversold with the relative strength index (RSI) sitting around 23 against spot June futures. Producers should develop a game plan for recovery that could allow for both adjustments on existing positions as well as new coverage further out on the curve to help weather the current storm.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

As we begin the new year, a lot of uncertainty remains following a tumultuous 2022, but there are reasons to be hopeful and optimistic. While spot margins are not favorable given the recent sharp selloff in hog prices combined with continued high feed costs, projected forward margins look very promising in deferred marketing periods. The current margin in Q1 2023 has deteriorated to a negative ($9.95/cwt.) which would represent the 3rd percentile of the past 10 years for any first quarter. As recently as last month, projected Q1 2023 margins were above the 80th percentile at $5.20/cwt. or higher, and there likewise was a previous opportunity to protect that level of profitability last August for this year’s first quarter. Coincidently, the projection for Q1 2024 is currently $5.27/cwt. which would be just above the 80th percentile of the past decade (Figure 1).

The contrast between this year’s Q1 and 2024 is very stark, a 10-year historical chart shows how infrequently margin values are either above or below either level (Figure 2).

Fundamentally, the picture is mixed as the pork cutout is down almost 10% from the end of last year and at its lowest value in the past 52 weeks. Weakness in bellies has been a big weight on the pork cutout as belly prices are down 35% from last year with freezer supplies swelling. The most recent USDA Cold Storage report pegged belly stocks at 63.06 million pounds at the end of December, up 15.9% from November and 65.7% above last year as well as 31.5% above the 10-year average (Figure 3).

By contrast, ham stocks are at a 10-year low of 53.4 million pounds, down 3.4% from November and 12.9% below last year as well as 22.4% below the 10-year average (Figure 4).

Export demand has been a bright spot with the year off to a solid start. For the week ending January 19 cumulative export sales reported by USDA’s FAS totaled 44,700 MT with both Mexico and China leading in volume sold. While down from the same pace a year-ago, exports are still very strong historically for the month of January, not far from a 10-year high. (Figure 5).

USDA updated pork supply and demand estimates in the January WASDE report, revising pork production higher for the first three quarters of 2023 while revising it down in Q4 relative to previous estimates. Q4 production is expected to be up almost 300 million pounds or +4.3% from last year, implying the USDA is expecting a big jump in the breeding herd as of March 1 and much higher September-November farrowings as well as a larger pig crop than the last report suggested. USDA is forecasting total pork production for 2023 at 27.495 billion pounds, up 485 million or 1.8% from last year.

There is growing optimism that the global economy may be in better shape than previously expected, particularly with China re-opening after sustained Covid-19 lockdowns. Stronger global demand and a weaker dollar which has also been a recent trend would be very helpful and welcome to sustain exports this year amidst increased production. All the same, growing production towards the end of 2023 into 2024 may threaten what are currently projected to be historically strong margins.

On the feed side, corn and soybean meal prices remain elevated as drought concerns in Argentina and strong demand from China are fundamentally supportive. While down from the past two seasons, projected Chinese corn imports of 18 MMT based on current USDA estimates would still be historically large, with an increasing share of that corn expected to come from Brazil (Figure 6).

Meanwhile, USDA trimmed their corn harvested acreage estimate in the January WASDE report to 79.2 million, the lowest since 2008-09 at 78.6 million which lowered production 200 million bushels from the previous estimate (Figure 7).

Soybean meal prices are very elevated also as strong demand and weather concerns likewise support the soybean complex. Longer-term, increased biodiesel production in the U.S. with new plants opening will divert more of the domestic crush to oil which will raise soybean meal supplies; however, this may also lead to more competition for acres which potentially could reduce the corn planting base. While the U.S. domestic crush projection for 2022-23 was left unchanged in the January WASDE report at 2.245 billion bushels, the figure would still be up almost 2% from last season to a new record high (Figure 8).

Fortunately, hog producers have a variety of ways to protect deferred margins using flexible strategies that allow for further margin improvement if hog prices move up, and/or feed costs come down. LRP might be an effective tool to protect deferred hog prices that may also have basis applications should cash prices prove particularly weak in Q4 and Q1 of 2024. Option strategies might also be employed that would likewise protect current hog values while preserving some degree of opportunity to participate in higher prices. Similar strategies can be used to protect higher potential feed costs while also maintaining the ability to realize a cost savings from lower prices over time.

Given the recent sharp deterioration in spot hog margins, producers should have added sensitivity about taking advantage of opportunities to protect favorable forward margins before they potentially deteriorate. Being proactive with risk management to secure forward profitability may prove prudent as the year unfolds in 2023. While it is impossible to know with any degree of certainty where prices are headed, it is important to realize that things often change unexpectedly, and these changes are not always favorable for margins. The past few years have presented numerous examples of how quickly things can change and disrupt profitability. The best offense is typically a good defense, and being defensive with margin opportunities is probably wise in the current environment.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

Halloween is a time of year when both kids and adults alike have fun being spooked but the hog market price action over the past month has been downright scary. December Lean Hog futures on the CME lost 18% in value over the second half of September, declining from $89 to $73/cwt. before recovering all of that lost value through October. As of this writing, the market has again turned down after facing resistance near the $90 level which has capped the contract on multiple occasions dating back to April. The feed markets by contrast have been steadier over the past couple months, although both corn and soybean meal continue to trade at historically elevated prices which has raised the cost of production and breakeven levels into 2023. From a margin standpoint, projected profitability in Q1 has seen an enormous swing with the recent hog market volatility, moving from a positive $5.00/cwt. around the 80th percentile of the past 10 years to a negative $8.50 earlier this month before recovering to back above breakeven (Figure 1).

Fundamentally, there is a lot to be optimistic about for the hog market which helps justify the recent price recovery. The September Hogs and Pigs report confirmed lower inventories including a decline in the breeding herd and forward farrowing intentions that will tighten supplies moving into next year. Moreover, producers are current as evidenced by recent trends in both slaughter weights and spot prices paid in the cash hog market. The latest Cold Storage report featured a contra-seasonal decline in pork freezer inventories, led by hams which at 159.3 million pounds were down 3% from August and 18% below last year (Figure 2).

A September drawdown in ham stocks is rare. 2019 is the only other occurrence in the past 15 years in which frozen ham inventories declined from August to September. It is interesting to note that the pork cutout contra-seasonally increased into mid-November during 2019 (Figure 3).

Turkey supplies are extremely tight this year following the Avian Influenza outbreak that hit commercial breeding flocks, and while ham prices are historically high, they remain competitive with turkey and an attractive alternative for Thanksgiving and Christmas celebrations (Figure 4). Strong export sales and shipments to Mexico are likewise supporting ham values, as the Mexican peso has not lost value to the USD despite the aggressive pace of monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve which has strengthened the dollar significantly in forex markets. Recently, exports sales have even picked up to other markets such as Japan and South Korea, two countries whose currencies have lost considerable value to the USD this year. Meanwhile, recent strength in Chinese hog prices has raised speculation that they will be more active buyers of pork on the world market ahead of the Lunar New Year, although a recent plunge in DCE hog futures prices and a significant slowdown in their economy due to the ongoing zero-Covid policy are concerning.

While overall the fundamental backdrop of the hog market is supportive as we move through Q4, one should not lose sight of the risks. The winter months historically have not been favorable for hog prices and the risk of recession here in the U.S. has risen significantly with the aggressive pace of Fed tightening. The potential impact on consumer spending should not be overlooked, and there are already indications that spending habits have changed for food consumed both at and away from home. Moreover, ASF remains a big risk factor and history has demonstrated that market reaction tends to be sharp and swift when disease issues suddenly disrupt exports.

With the recent recovery in both hog prices and forward margins, it may be prudent to look at strategies to mitigate downside risk, particularly for those who may be light on coverage in 2023. Given the potentially supportive fundamental backdrop, strategies that retain flexibility to participate in higher hog prices and improved margins may be prudent to consider. Livestock Risk Protection (LRP) insurance may be a cost-effective way to put a floor under the market while allowing for the possibility to capture any further price advances. In addition to the reduced cost and cash flow advantages with this type of coverage, there may also be basis management applications that would be advantageous for Q1.

As an alternative to LRP, option strategies may likewise make sense to retain upside price flexibility while helping to put a floor under the market and protect against negative margin outcomes. While exchange-traded alternatives may be more costly than using LRP, the expense could be reduced by accepting a cap above the market which would correspond to historically high hog prices and strong margins should the market reach that threshold. As with any strategy, it is important to strike a balance between risk and opportunity that allows your operation to manage margin volatility and achieve long-term goals. The market has provided another opportunity to help mitigate forward exposure and it may be wise to take advantage of it.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

As we work through the dog days of summer, there seems to be no shortage of optimism among many hog market participants. Much of this exuberance is rational given strong domestic demand, lower sow inventories across the U.S., EU, and China, and the expectation of stronger pork exports in the last half of the year. Cash hog prices have been advancing throughout the summer while corn and soybean complex prices have perhaps found seasonal bottoms over the past couple weeks. While these factors support hog margins, we know market dynamics can, and often do, change quickly. It is natural to focus on the bullish narrative of the market, but discipline should be exercised as we begin looking at establishing margin coverage at historically strong profitability in deferred periods.

Hog Market Considerations

The bullish case for hogs is compelling but continued headwinds on the trade front could complicate matters. Compared to last year, USDA projects U.S. pork production to fall 1.9 percent in 2022 while they peg 2023 production to increase only 1.3 percent year-over-year. Domestically, retail pork prices continue to set new record highs but remain near their long-term average as a share of retail beef prices. Of course, for a sector that exports a quarter of its production, no story on pork demand can be complete without looking at international trade. USDA projects 2022 pork exports to fall 6.4 percent from 2021. Through May (the most recent month for which complete data is available), pork exports were down 20 percent from a year earlier. Of the major trading partners, only Mexico has posted year-to-date gains from 2021.

Figure 1. U.S. Pork Exports

China’s reduction in imports from all sources has weighed on global pork trade in general and the strength of the U.S. dollar is making American product more expensive for foreign consumers. China’s slowing economy, coupled with the prospect of a recession on the horizon, could reduce international demand. USDA forecasts 2023 per capita pork consumption to be 52.4 pounds per capita. If realized, this would tie the highest level witnessed since 2000, but it is important to remember any disruption in or destruction of export demand will only exacerbate the onus put on the domestic consumer next year.

Figure 2. China Pork Exports

If the last several years have taught us anything, it is that things can change in a hurry. The CME lean hog index has been on a steady march higher since mid-May and is approaching levels last witnessed in June 2021. The PED-impacted summer of 2014 is generally held as the gold standard of the height to which hog prices can reach, but oftentimes missing from that discussion is how short-lived that price environment ended up lasting. The market scored a low in January 2014, increased through April, pulled back into June, and ran out of steam by mid-July. While the run-up in hog prices was rapid, the retreat was swift, as well. The domestic hog herd was rebuilt as producers responded to market signals. At the same time, labor disputes at West Coast ports caused major disruptions to international trade in the second half of 2014 and early 2015. One cannot help but draw a parallel between the port slowdowns from 8 years ago and the bottlenecks in supply chains we are experiencing today.

Figure 3. Historical Daily Lean Hog Index

Feedstuff considerations

New crop futures contracts gave up Ukrainian war and weather premium over the past several weeks to return to levels last witnessed in February, offering end users a chance to protect more favorable price levels. Corn futures prices have been in reprieve since mid-June as concerns about late plantings were largely mitigated and timely rains arrived in the heart of the Corn Belt. Overall, the market fell about $2 per bushel from the mid-May high through mid-July. It is difficult to know where we go from here, but it is typical for the December contract to find a bottom in late summer. Crop condition ratings overall are slightly behind year ago levels on a national scale but remain significantly behind a year ago in the eastern Corn Belt and the High Plains.

Figure 4. Corn Conditions Map

According to CFTC data, the non-commercial long position is at a multi-year low. This all comes against the backdrop, of course, of tremendous uncertainty in the form of conflict in Ukraine, La Niña-induced dryness in South America, and expanding drought in the EU. The global corn exporter balance sheet is historically tight and there appears to be little room for yield loss this year or next, so long as product from the Black Sea cannot find its way to the world market.

Figure 5. Corn Exporter Stocks-to-Use Ratio

New crop soybean futures have followed a similar trajectory to corn. The recent pullback has uncovered demand from overseas buyers. USDA reported flash sales to China last week for the first time since June 1 and new crop soybean sales to China are at their highest level for this point in the year since 2013. Crop conditions are similar to a year ago with marked improvement across the Dakotas, but we know August weather is a vital determinant of yield potential. Weather across the central U.S. will continue to take center stage over the next few weeks. Like corn, the soybean exporter balance sheet is historically tight.

Figure 6. Soybean Exporter Stocks-to-Use

The soy complex is also in the midst of a radical change and livestock producers will likely reap the benefits. The push for renewable diesel to reduce carbon emissions has spurred a flurry of investment in crush plants across the country. The expectation is the influx of demand for soybeans and bean oil will result in increased availability of meal, driving meal costs lower. It is important to remember, however, that many of these plants are not set to come into fruition until late 2023 or 2024. While these developments could be beneficial for soybean meal buyers, it may not be fully realized for another crop year or two.

Risk Management Implications

With the geopolitics, weather, and the other market forces outlined above making headlines on a daily basis, it is easy to not see the forest for the trees. Forward profit margins on our demonstration operation have rebounded from lows scored in mid-May and are offering producers a chance to protect historically strong profitability through Q3 2023. We are near or above the 75th percentile of historical profitability over the past decade for the next 12 months.

While potential remains for margins to continue higher if the bullish fundamentals outlined above come to fruition, significant risk to the downside remains. Most producers are unwilling to completely lock in margin levels today with futures purchases and sales due to fear of missing out on higher margins. Flexible strategies can be employed to allow for margin improvement while providing protection against adverse movements in hog prices, corn and meal prices, or a combination of the three.

Figure 7. Q3 2023 Margins

Objectively assessing margin opportunities in the future is the first step to determine whether they are worth protecting. It also helps remove the constant noise in the marketplace. Discipline is at the core of every sound risk management approach. Producers have been given a chance to remove significant risk from their operations over the next year while maintaining opportunity to the upside through flexible coverage. For more help on evaluating specific strategy alternatives or to review your operation’s risk profile, please feel free to contact us.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

For many of us involved in the pork industry, the turn of the calendar to June means World Pork Expo is once again upon us. The event serves as the unofficial start to the summer season for many stakeholders and allows us all the opportunity to catch up in person with friends, colleagues, and industry professionals.

We most look forward to the conversations we will have—many of which will likely expound on topics such as domestic disease mitigation, Chinese demand, and tight global grain and oilseed balance sheets. Each of these areas are critically important and have been covered at length in trade publications over the past several years. But another topic that warrants discussion at this year’s gathering is the good work done on behalf of livestock producers by USDA’s Risk Management Agency and its Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC).

USDA has offered two livestock insurance products for swine producers for nearly two decades. Livestock Risk Protection (LRP) is an insurance product designed to protect against a decline in market price. Livestock Gross Margin for Swine (LGM) provides protection against the loss of gross margin of swine (market value of livestock minus feed costs). Several rounds of LRP and LGM modifications approved by the FCIC over the past two years have made the insurance products a valuable component to many producers’ toolbox to manage risk. These changes have broadened the appeal to producers by increasing premium subsidies, increasing head limits, extending endorsement lengths, and easing the strain on producer cash flows. As a result, participation in the insurance programs has increased substantially.

Figure 1. Participation Growth in LGM and LRP

The most recent round of LRP revisions, announced in April 2022, continued to build upon recent improvements and will likely increase participation in these important programs. One modification increased both endorsement and crop year head limits beginning in Crop Year 2023, which runs from July 1, 2022 to June 30, 2023. Previously, the limit per swine endorsement was 40,000 head, or 150,000 head per producer for each crop year. Recent modifications increase those limits to 70,000 head per endorsement and 750,000 head per crop year. This amplified the number of animals that could be protected from future market price declines, substantially bolstering the safety net for hog producers. There has never been an annual head limit on LGM-Swine.

Several of the changes announced were designed to increase options at producers’ disposal. Whereas livestock producers previously had to choose between one program or the other, they can now use both. An insured may not, however, insure the same class of livestock with the same end month or have the same insured livestock insured under multiple policies. This allows for flexibility in decision making and lets producers make the best choice for their own financial situation and their own operation. LRP policies were also changed to allow any covered livestock to be “marketable” (meet a minimum weight requirement) by an endorsement’s end date. Previously, protected swine actually needed to be marketed within 60 days prior to the end date or maintain ownership on the end date.

Recent modifications also were geared toward allowing a wider array of ownership structures to participate in the program, better reflecting the diversity of participants in the pork production sector. Past policy language stated that only producers who owned sows under the same entity that owned and marketed the finished swine were able to purchase LRP for Unborn Swine. This limited the number of producers who could protect future swine marketing beyond 6 months out in time. This policy now states that the sows do not have to be owned in the same entity name as they are marketed. Proof of ownership prior to the issuance of an indemnity is also required, bolstering the integrity of LRP.

Additional changes to the programs include reducing the time limit for insurance companies to pay indemnities from 60 days to 30 days, clarifying how head limits are tracked when an insured entity has multiple owners, providing insured producers greater choices in how they receive indemnities, and modifying the endorsement length for swine to a minimum of 30 weeks for unborn swine and a maximum of 30 weeks for all other swine. These improvements to both the LRP and LGM programs have allowed for reduced costs and increased flexibility to the producer, taking two relatively unused programs and making them widely available across the industry to producers of all sizes.

We view these insurance products as important additions to producers’ toolbox to manage margins over time. It is important to note that the decision to use LRP is not an either/or decision with exchange-traded instruments. Many producers have also found utility in pairing the LRP coverage as the root of other futures and options strategies. With tremendous uncertainty and volatility proliferating throughout the equity and commodity markets today, establishing floors via subsidized insurance programs could make a lot of sense for many farmers.

A prime example of how one could implement LRP or LGM as part of a risk management strategy is looking at open market hog margins toward the end of the year. Despite multi-year highs in corn futures and elevated soybean meal prices resulting from conflict in Eastern Europe, dryness in South America, and a slower-than-normal domestic planting pace, open market margins for the 4th quarter offer producers the chance to protect slightly better-than-average profitability. Looking at the chart below, there is a very strong seasonal tendency for both December lean hog futures as well as 4th quarter margins to fall from early June into the first week of August.

Figure 2. December Lean Hog 10-Year Seasonality

Figure 3. Q4 Open Market Hog Margin 10-Year Seasonality

While many producers may not be willing to simply lock in these margin levels with straight futures purchases and sales, some may be willing to establish protection with floors and maintain opportunity to the upside using either of the insurance products. The seasonal charts above indicate it could be timely to do so over the next several weeks. On the one hand, the latest Hogs and Pigs report indicated a continued reduction in market hog availability compared to a year ago. On the other hand, continued lackluster export demand or crop production issues could squeeze the better-than-average open market margins being offered today. LRP or LGM could be a great start in establishing coverage given current margin levels and the seasonal tendency for margins to fall over the next two months.

The sign-up process for LRP and LGM is simple and program costs are uniform across all agencies. The value the agent brings is their expertise, tools, and analysis. Contact us or visit us at Booth V361 in the Varied Industries Building at this month’s World Pork Expo to discuss effective applications of these tools and how these programs could fit into your risk management approach.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

Hog margins have steadily improved since the beginning of the year. Futures markets are projecting the highest forward-looking hog margins for a model operation since 2014. Taking Q2 as an example, current margin projections are about $25/cwt., one of the highest projections for this quarter over the previous 10 years, and the highest for this point in the calendar year since 2014 when margins peaked at about $50/cwt. during the first week of March.

The opportunity to protect historically rare margin levels comes on the heels of a red-hot hog market, despite corn and soybean complex futures notching multi-year highs. The strength in feed markets has been quite remarkable, and it is important to realize the impact this has on profitability. Since the beginning of October, the nearly $1.00/bushel rise in corn and $100/ton increase in soybean meal have combined to reduce margins by about $8/cwt. for Q2, even though projected margins have improved almost $9/cwt. overall since then. The increase in projected hog prices has more than offset the increase in feed costs.

While you may believe the opportunity to the upside for hogs outweighs the risk to the downside, it may be prudent to protect forward profitability, particularly in deferred periods where margins could end up being weaker than current projections. Q3 2022 hog margins are currently just below $20/cwt., and like Q2, are in the top decile of the previous decade at the 93rd percentile of the past 10 years. While both Q4 and Q1 2023 margins are comparatively weaker from a historical perspective, they are nonetheless above average and close to the 80th percentile of the previous decade. Moreover, we are moving into a seasonal period where it has historically been beneficial to protect winter margins as they tend to peak during the spring.

While feed costs are already quite high, a further rise in prices could pressure forward profitability during a period when it may be more difficult for hog and pork prices to keep pace. The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine adds a whole new risk dimension to the global supply/demand outlook. The slowing of Ukrainian corn flow is a major potential issue in a tightening global balance sheet situation. Tension in the Black Sea region introduced new volatility to the market over the past several weeks.

While there are a multitude of knock-on effects from the escalation, the corn market has been particularly impacted. According to the latest WASDE report, USDA projects Ukraine to account for 17 percent of global corn exports. Ukraine on February 24 suspended commercial shipping at its ports after Russian forces invaded the country. While it is unclear the impact this will have long term on the Eastern European country’s ability to supply grain to the world, futures markets were limit up in the immediate aftermath of the invasion.

Moreover, the major corn and soybean exporter stocks to use ratios are historically low, and this magnifies the risk from uncertainty in the aftermath of Ukraine’s situation. Major corn exporter stock-to-use for the 21/22 crop year of 8.4 percent in the latest WASDE is well-below the average over the past decade. It is important to note this figure accounts for record corn production in both Argentina and Brazil, where La Nina has significantly impacted crop planting and conditions. Most analysts expect the South American crop to continue shrinking, putting further pressure on an already tighter-than-average global balance sheet.

Likewise, the global soybean balance sheet is also historically tight. USDA last projected the major soybean exporter stock-to-use ratio at 16.8 percent. If realized, this would be the lowest level since 1996. Similar to corn, USDA has been shrinking South American soybean production in each of the last two WASDE reports. Crop conditions in both Brazil and Argentina continue to struggle, opening the door for a continued tightening of the global balance sheet.

The fertilizer market is another risk factor for corn which could significantly impact the domestic supply/demand balance sheet for the upcoming crop year, particularly if the weather is unfavorable during the planting and growing season. Russia is the second largest nitrogenous fertilizer exporter to the US and nitrogenous is the second most imported type of fertilizer. Corn typically requires applications of all three nutrients (Nitrogenous, Phosphatic, Potassic), while soybeans typically only need Phosphatic and Potassic. If the Russia/Ukraine conflict leads to lower supply/higher priced Nitrogenous fertilizer, there could be more incentive to either plant soybeans over corn or use less fertilizer on the corn which would decrease yields and production.

The US imports approximately 27% of the domestic nitrogen supply, with imports sourced from Canada (19%), Russia (18%), Qatar (14%), and Trinidad and Tobago (10%). Russia recently set 6-month quotas on phosphate fertilizers, further stressing the global market. Russia accounted for 10% of global processed phosphate exports in 2020. Potassium is also important for corn growth as it aids in disease resistance and water stress tolerance. The US imports the vast majority of its potash consumption annually with imports sourced from Canada (85%), Belarus (6%) and Russia (6%).

The USDA’s Outlook Forum recently estimated 2022/23 US corn ending stocks at 1.965 billion bushels, up 425 million from this year with a stocks/use ratio at 13.2% which if realized would be the highest since the 2019/20 crop year. The projected season-ending corn price received by producers was forecast down 45 cents from the current year to $5.00/bushel. Obviously, there are a lot of assumptions in this forecast including trendline yields and normal growing conditions. The good news is that despite currently high feed prices there are margin opportunities, and it may be prudent to take advantage of these opportunities including the protection of feed input costs.

To take advantage of opportunities, it is important to know where your margins are. By taking account of your various input costs and expenses and projecting hog sales revenue against those, you can begin tracking forward profitability and put that into a historical context. This will allow you to objectively determine favorable opportunities to initiate margin protection and shield your operation from either rising feed costs or declining hog prices. While no one can know for certain what the markets will do as we move forward in time, it is probably safe to say that we can expect more volatility given increased uncertainties.

Trading futures and options carries a risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Insurance coverage cannot be bound or changed via phone or email. CIH is an equal opportunity employer and provider. © CIH. All rights reserved.

The CARES Act was passed by Congress to provide quick and direct economic assistance to Americas to combat the economic impacts of COVID-19. The Act also directed the USDA to administer the newly-created Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). CFAP has two components. The first is the Farmers for Families Food Box program, which uses $3 billion to prepare and deliver emergency food boxes to food pantries across the country. The second component of CFAP is direct payments to agricultural producers. While much has been written about the direct payments to eligible producers, there remains a degree of confusion regarding payment rates and calculations.

Beginning May 26, USDA’s Farm Service Agency will be accepting applications from agricultural producers who have suffered marketing losses due to COVID-19. The program, announced May 19, provides assistance to producers of eligible commodities that have suffered a five percent (or greater) price decline as a result of the pandemic. The direct payments program requires one application and results in a single benefit, but the funding and legislative authority derives from two separate programs. The dual sources of funding have caused some confusion among stakeholders but are further outlined below. This allows for a larger level of payment to be delivered than either single program could provide. USDA estimates the first source of funding, the CARES Act, will account for about $9.5 billion in CFAP payments. The other source of funding, the Commodity Credit Corporation, will account for an additional $6.5 billion in payments. The CCC is a business entity with the USDA and was created under the New Deal, providing the Secretary of Agriculture with broad and discretionary authority for various purposes, including direct payments. Calculations for covered commodity categories are included below.

USDA will make an initial payment of 80% of the eligible 2020 CFAP participant’s calculated 2020 CFAP payment. This allows for checks to be delivered to farmers quickly and allows for USDA to evaluate how well the program is performing compared to expectations. There is a possibility the final 20% could be subject to pro-rationing, depending how close to expectations initial payments end up.

Farm Service Agency staff at local USDA Service Centers will work with producers to file applications. CFAP payments are subject to payment limitations per person or legal entity of $250,000. This cap is on total CFAP payments for all eligible commodities. Direct payment limits also apply to LLCs, corporations, and limited partnerships. These entities may receive up to $750,000 based on the number of shareholders (not to exceed three shareholders) who contribute at least 400 hours of active person management or personal active labor. To be eligible for payments, the person or legal entity must have an adjusted gross income of less than $900,000 for tax years 2016, 2017, and 2018 or demonstrate that 75 percent of their adjusted gross income comes from farming, ranching, or forestry.

Livestock

Cattle, hogs, and sheep are included in the CFAP direct payment program. The components of the livestock CFAP payment are as follow:

- CARES Act funding is used to compensate producers for price losses on sales of eligible livestock from January 15 through April 15

- CCC funds are used to compensate producers for the highest inventory of eligible livestock between April 16 and May 14

For example, consider a cattle feedlot with sales of 800 fed cattle from January 15 through April 15 and a maximum inventory of 400 head from April 16 through May 14. The producer’s CFAP payment would be calculated as follows:

((800 x $214) + (400 x $33)) x 80% = $147,520

Consider a hog farmer with 7,200 head in sales of finished animals from January 15 through April 15 and a maximum inventory of 4,800 head from April 16 through May 14. The producer’s CFAP payment would be calculated as:

((7,200 x $18) + (4,800 x $17)) x 80% = $168,960

Dairy

Milk production is also included in the CFAP direct payment program. The components of the dairy payment are as follow:

- CARES Act funding is used to compensate producers for price losses during the first quarter of 2020. This value is equal to $4.71 per hundredweight multiplied by actual milk production in the first quarter.

- CCC funds are used to compensate producers for marketing channel disruptions for the second quarter of 2020. This value is based on a national adjustment to each producer’s production in the first quarter multiplied by $1.47 per hundredweight.

In other words, the first component compensates for value lost on actual first quarter production and the second component compensates for value lost on a calculation of second quarter production. The second quarter production is calculated by multiplying the first quarter production by 1.014 (to account for increased production in the second quarter). It is expected milk production will be established in the same manner as was used for Dairy Margin Coverage. Generally, this includes cooperative- or processor-verified documentation for marketings of milk and includes dumped milk that was pooled under a federal marketing order.

Milk production is also included in the CFAP direct payment program. The components of the dairy payment are as follow:

For example, for a dairy farmer with 400 cows and 2,440,000 pounds of milk production in Q1 2020, his CFP calculation would be the following:

((24,400 x $4.71) + (24,400 x 1.014 x $1.47)) x 80% = $121,035

Non-Specialty Crops

CFAP direct payments are also available for eligible producers of non-specialty crops that have suffered significant price decline due to the pandemic. The source of the non-specialty crop direct payments also comes from two sources—CARE Act funding and the CCC program. Payment rates for each commodity are included below.

A direct payment will be made based on 50 percent of a producer’s 2019 production or the 2019 inventory as of January 15, whichever is smaller. The smaller value is multiplied by 50 percent and then multiplied by the commodity’s applicable payment rates.

For example, consider a corn farmer who had production of 800,000 bushels in 2019 and on January 15 had 500,000 bushels in inventory. The first step in calculating the CFAP payment is to determine the smallest value between 50 percent of 2019 production (50% x 800,000 = 400,000 bushels) or January 15 inventory of 500,000 bushels. Because 50 percent of 2019 production is smaller, 400,000 bushels is used for the first variable. The rest of the calculation can be found below:

400,000 bushels x 50% x ($0.32 + $0.35) x 80% = $107,200

If the same farmer instead had only 250,000 bushels in inventory on January 15, the calculation would change. Because 200,000 bushels is less than 50 percent of the 2019 production (50% x 800,000 = 400,000 bushels), the inventory value would be the first variable in the calculation:

250,000 bushels x 50% x ($0.32 + $0.35) x 80% = $67,000

The USDA’s Farm Service Agency is the entity charged with interpreting and carrying out the final rule. The aforementioned information is an attempt to bring clarity to the program based upon our reading and interpretation. Additional information on the program can be found at https://www.farmers.gov/cfap.

What is the best way to determine the fair market value of a pig? This seemingly innocuous question has resulted in a multitude of opinions over the years as market dynamics, participants, and trends change. As the volume in the negotiated market has dwindled, some market participants have noted the rise in the use of cutout-based contracts to price hogs. But given the large amount of information published by USDA on a daily basis, how is the carcass cutout calculated and what can be gleaned from the various cutout reports?

Wholesale pork reporting as part of the USDA’s Livestock Mandatory Reporting Program (LMR, or oftentimes referred to as MPR) began in 2013 at the request of industry participants. USDA AMS publishes four daily and eight weekly pork reports from their Des Moines office by analyzing 8,000-10,000 records per day. These reports cover approximately 87% of total pork sales. All packers slaughtering more than 100,000 head of barrows and gilts (or more than 200,000 head of sows and/or boars) annually are required to report the prices and quantities of all wholesale pork sold prior to the established reporting times to USDA twice daily.

The pork carcass cutout value is a calculation of the approximate value of a carcass based on the prices received for its respective components. The USDA’s pork carcass cutout value is the estimated value of a standardized 55-56 percent lean, 215-pound carcass based upon industry-average cut yields and average market prices of sub-primal pork cuts. In other words, weighted average prices of individual items are used to calculate a weighted average value for primal cuts. The primal cut values are then used to calculate a carcass equivalent value. USDA surveys packers in July and updates the cut yields the following January if necessary. The current yields can be found below. The loin primal constitutes the largest share of the cutout value, followed by the ham, and so on.

While it is important to understand what is included in the cutout calculation, it is also vital to understand what is not. Not included in LMR reports are carcasses, some variety meats (including ears, hearts, blood meal, cheek meat, and heads), some processed items (including bacon, sausage, ground pork), case ready items, and intracompany sales.

The National Weekly Comprehensive Pork Report (LM_PK680) includes the comprehensive value and volumes of all reported wholesale pork trade with the exception of specialty pork product and is a great resource, but unfortunately did not begin until May 23, 2019. Its use for looking at long term trends is therefore limited but is an important report moving forward. One last note—FOB plant prices are as reported by the packers at their dock before transportation costs have been added. USDA also publishes FOB Omaha prices series, which are an antiquated data set that include a freight adjustment based on the distance from the reporting plant to Omaha, Nebraska. Most market participants utilize FOB plant for formulas and analyses today, of which USDA AMS publishes four national weekly pork reports:

- Negotiated Sales (LM_PK610): price determined by seller-buyer interaction and agreement, scheduled for delivery not later than 14 days for boxed product and 10 days for combo products after the date of agreement.

- Formula Sales (LM_PK620): price is established in reference to publicly available quoted prices.

- Forward Sales (LM_PK630): agreement for sale of pork beyond the timeframe for a negotiated sale.

- Export Sales (LM_PK640): as its name implies, contains sales to export markets. Unlike the other three, however, this report does not include sales to Canada or Mexico.

Each load reported in the cutout reports represents 40,000 pounds. Formula pork sales reported on the LM_PK620 report represented about 53.2% of all reported pork wholesale volume in 2019, followed by negotiated sales (25.3%), export sales (11.4%), and forward sales (10.0%).

As exports play an ever-increasing role in price discovery, an often-overlooked source of information is included in the LM_PK640 report. This data has the potential to provide an indication of export demand developments well ahead of the official figures from the U.S. Census Bureau. A single data point does not make a trend, but it is interesting to note that during the first week of the Phase One trade deal with China, the weekly volume reported on the LM_PK640 report was the 5th highest since the beginning of 2014. This data is released on Monday mornings for the week preceding, as opposed to the FAS Weekly Export Sales reports which are released on Thursdays for the week ending the preceding Thursday and official export figures which are lagged by at least five weeks.

Because a spike in volume on the LM_PK640 report could indicate robust demand, forward domestic volume as measured by the LM_PK630 Forward Sales report can, and oftentimes is, also impacted. For example, amidst robust export pork sales beginning in late September and lasting through mid-November, a perceived forward market shortage sentiment developed among participants. As a result, forward wholesale pork sales volume also posted all-time highs for the data series.

This competition for securing physical led to a counter-seasonal rise in the cutout during a period of record-breaking hog slaughter, as can be viewed below. The first chart demonstrates how the cutout typically declines from a time period beginning in the summer months into the holiday season. In 2019, however, the negotiated cutout value increased by more than 27% from September through mid-November.

The pork carcass cutout calculations produced by USDA AMS provide utility to market participants and offer context to marketplace fundamentals. Utilizing these reports may reveal perceived strength or weakness in cutout sales and provide glimpses of market conditions ahead of other more frequently leveraged data sources. As producers continue to search for the best method to determine a fair market value for their animals, it is important to understand the difference between the various cutout reports, what is included in their calculations, and what is omitted. These reports are another essential tool to employ to obtain greater clarity in an ever-dynamic, evolving marketplace, gather clues into forward demand, and potentially leverage to take control of your bottom line.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.